Dr Sherrington Gilder

In 1915 an Australian newspaper, ‘THE BRISBANE COURIER’, carried a notice in their obituary column:

“Death on 30th July of Marie Gilder, relict of the late Dr Sherrington Gilder MD, FRCSL, and daughter-in-law of the late Dr Sherrington Gilder, surgeon in the Coldstream Guards”[1].

How little of the full story those few formulaic words encompassed.

Sherrington Gilder (b.1843) could easily have been known as Alfred rather than Sherrington. His siblings were named, in order of birth, Alexander, Archibald, Arthur, Algernon, Angela, Aurelius, Amy, Augusta, Amelia and Albert. He was the fifth-born and baptised Alfred as his first Christian name but he was also given the name of his father “Sherrington” Gilder MRCS (1798-1874), and by the name Sherrington he was subsequently known.

Sherrington Gilder senior was a surgeon in the 2nd Regiment of the Life Guards (not the Coldstream Guards as stated above). He had seen service at the battle of Waterloo when he would have been 17. It was his older brother Frederick (1794-1876) who was similarly employed in the Coldstream Guards. Their father James Gilder was also a military doctor, a career perhaps not entirely for the faint-hearted at that time despite the encouragement of it being ‘the family business’[2].

The senior Sherrington led a peripatetic life possibly due to his military career or perhaps due more to his sheer love of non-conformity and adventure. His first son was born in France in 1828 by his wife Sarah Treadcroft whom he had married in 1821[3]. But thereafter as he travelled throughout Europe, whether in France, Italy (where Sherrington junior was born – in Lucca, Tuscany), Devon or London, his children were born over the next twenty years by another woman – Maria Hunter whom he eventually married three months after the death of Sarah in 1852. He was 60 when his last child was born in 1859 and in that year some of the older children were finally baptized. In 1867, at the age of 68, he emigrated from Thanet, Kent with most of his family on an “assisted passage” to Australia. He settled in Sydney where the family began to establish themselves and where he died some years later on 8th January 1874[4].

Not long after the family arrived in Australia, Sherrington junior (24) met and married, in 1867, Gertrude Marie Keane (22), in Melbourne. Over the next 10 years they had four children, Ione, Harold, Beatrice and Hilda. That might have been the end of the story except that at the end of those 10 years, in 1877 we find him back in England, in Liverpool, where he is getting married again. This time, on 23rd March, he took as his wife Elizabeth Blackwell (18), youngest daughter of a Cheshire salt manufacturer, James Blackwell of Newton Lodge, Middlewich. Their first child Helena was born in Beverley, Yorkshire a year later in 1878, which coincidentally is the year recorded for the birth of his fourth Australian child. Seemingly he abandoned his Australian family (including a pregnant wife) to return to England after the death of his father. He came back to England to complete his medical studies like his father and grandfather before him, but unlike his father he bigamously married a second wife, the mother of his second family.

In 1879 he was credited with the Licentiate examinations of the London Society of Apothecaries (St. Thomas’ and Paris) thus enabling him to practice medicine as a General Practitioner[5]. His second (English) daughter Dora was born in Beverley, Yorkshire that year. Professionally, and also in that year, Dr Gilder was called upon to give evidence at the inquest on the sudden death (pulmonary embolism) in Beverley of a young woman aged 21[6].

Their son Francis was born the following year by which time the Gilders had moved to Earl Soham, east of Stowmarket in Suffolk where he was working as a locum tenens in the practice of Dr Fletcher. Dr Fletcher was ill and had gone to Italy to recuperate. Dr Gilder was very much at the beginning of his medical career but for public consumption he was referred to as a ‘partner’ in the Earl Soham practice. In fact he was paid a fixed salary of £160 per annum by Dr Fletcher, in quarterly instalments. In February he gave evidence at the inquest on Robert Read of Kettleburgh whose death from kidney disease was triggered by his falling through the ice when getting water for the stock under his charge[7]. In March that year he also gave evidence at the inquest on the death of a new-born infant in the village[8]. Also In that year he completed his medical qualifications with his “LRCP”: Licentiate of the Royal College of Physicians[9].

Following the sudden departure of Dr Short from Walsham Le Willows in 1881 it fell to Philip Youngman, one of the ‘Guardians of the Poor’ of the village, and a leading figure in the Walsham community to organise a replacement. Mr Youngman lived at The Rookery and was a substantial farmer. The census report of 1881 showed him as farming 377 acres and employing 10 men and 5 boys which would have been one of the largest holdings locally. The Youngman family were also influential members of the Non-Conformist community and also the Temperance movement. Having taken soundings – and the general consensus of the village being that it was an appropriate move – he wrote to Dr Gilder at Earl Soham to offer him the job of doctor for the people of Walsham Le Willows.

The financial aspects of the move concerned Gilder as he would, at least temporarily, have to pay for his replacement locum at Earl Soham and the rental of the furnished house there for his family. He pointed out that he had no financial means and would require credit from the local Walsham tradespeople at least initially. This was potentially contentious following their late experience with Dr Short. Arrangements were discussed and agreed, and to seal the deal Mr Youngman offered to lend him the money (at 5% p.a. interest) to pay the outstanding arrears on Dr Short’s lease of The Beeches. He also offered to drive him about and introduce him to the local inhabitants, and also to provide temporary accommodation for him in his own house while the necessary arrangements were made at The Beeches. There would be no premium paid to Dr Short (or rather his creditors) for the goodwill of the practice. Thus Dr Gilder would better himself by leaving Earl Soham and taking over the medical practice in Walsham, and also the rental of Dr Short’s house[10].

In April 1881 he moved into The Beeches where he both lived and had his surgery. That month he was immediately elected by the Guardians of the Stow Union as Medical Officer and Public Vaccinator for the District of Walsham le Willows which would be of at least some help financially[11]. For another assured income stream he also became Medical Officer of the local Court of the Ancient Order of Foresters and no doubt in that role attended their annual fete and gala which in July took over the village for a day of great celebration[12]. At the formal dinner that evening he was called upon to make the reply to the Toast of ‘The Army, The Navy, and the Reserve Forces’ in which he alluded, at least in part, to his own family history.

The Gilders proceeded to involve themselves in Walsham village affairs. In November they both participated in an ‘Entertainment’ at the “Town Hall” where Dr Gilder’s contribution was a reading of ‘The Charge of the Light Brigade’[13]. Mrs Gilder sang two songs in the programme, ‘Home Sweet Home’, and ‘The Angel at the Window’’, the maudlin sentimentality of both of which going down well with the audience: the songs were encored.

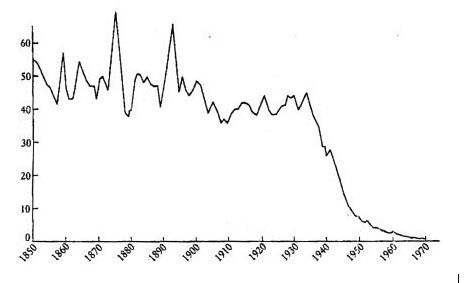

In July of the following year a fourth child Christian Lilla was born to the couple but tragically within a month the child’s mother died. Bessie was aged 24. The Walsham Church records for 1882 note both the baptism and the burial in poignant proximity[14]. Despite on-going medical progress including the pioneering antisepsis work of Ignaz Semmelweis (1847) rates of perinatal death remained stubbornly high in Britain until well into the 20th century.

His wife’s early death obviously came as a severe loss to Dr Gilder and his young family and one can only speculate as to the support he needed and got. But within a year the family had left Walsham. He sold the practice for £450 to Dr Frederick McNaught (26) from Ireland and moved to London where he lived at various addresses in Acton and Wandsworth. He had at least one brother living in London.

There was a brief and rather unfortunate postscript to his time in Walsham when he was subjected to a lawsuit by Mr Youngman. The papers were initially served in London for a superior court but the action was sent down for hearing back in Bury St Edmunds Crown Court before His Honour Judge Francis Roxburgh QC on 23rd September 1884.[16] Dr Gilder was sued by Mr Youngman for payment of £25 8s.4d. “for six weeks board and lodging, use of pony and trap etc.” This was payment for the time he lived at The Rookery upon his initial arrival in Walsham. It may seem extraordinary that the two men whether through stubbornness or moral principle or some other reason were prepared to publically go through a detailed and expensive examination of their private affairs on a relatively minor issue. It was established that Dr Gilder had arrived in Walsham “with only 11 pence in his pocket”. Mr Youngman had agreed they would provide a bed for him – “the best bedroom”, and also a room in which to conduct his surgery on a temporary basis. Mrs Youngman had however adamantly refused to agree to provide him with food. Nevertheless having been invited to breakfast on his first day he subsequently enjoyed four meals a day “without being invited” and on leaving told Mrs Youngman he had “never been so comfortable in his life”. There was much debate as to what if any payment for this hospitality had actually been agreed. The story having been examined in exhaustive detail by the court, the judge found for the plaintiff.

Dr Gilder lived until 1901 when he died at the age of 58. He had married again in 1891, this time to Florence Hilder (31). They had no children. He set up practice in Tunbridge Wells where he and his wife lived before moving subsequently to Hastings. In his final years he suffered from ill health and was unable to work. In 1899 it was reported that he was a permanent invalid “suffering from spinal disease”[17].

Florence survived him for many years living on the south coast in modest gentility while Marie, as we have already seen, died in Australia in 1915.

Joseph McCann

January 2018

References

[1] THE BRISBANE COUIRIER 7thAugust 1915

[2] James and his wife Susanna both died in Fontainebleau, France in 1826

[3] MORNING POST 22nd May 1821.Marrried – yesterday May 21st at Marylebone Church, Sherrington Gilder Esq to Sarah, youngest daughter of N. Treadcroft Esq of Horsham, Sussex

[4] THE BELFAST NEWSLETTER Saturday 14 March 1874

[5] THE MEDICAL TIMES AND GAZETTE 1879

[6] YORK HERALD Monday 15 December 1879

[7] EAST ANGLIAN DAILY TIMES Saturday 5th February 1881

[8] FRAMLINGHAM WEEKLY NEWS Saturday 5th March 1881

[9] THE MEDICAL DIRECTORY 1900

[10] THE MEDICAL TIMES AND GAZETTE 1882

[11] BURY FREE PRESS Saturday 23 April 1881

[12] BURY FREE PRESS Saturday 9 July 1881

[13] BURY AND NORWICH POST Tuesday 29 November 1881

[14] NORTHWICH GUARDIAN Saturday 19 August 1882

[15] CHAMBERLAIN, Geoffrey: British maternal mortality in the 19th and early 20th centuries, JRSM (2006 Nov)

[16] BURY AND NORWICH POST Tuesday 30th September 1884

[17] MORNING POST Friday 4th August 1899