The Hawes of Walsham le Willows – A Probable Family History (Part One)

Hawes is one of the very early names associated with Walsham and certainly ancient in origin. The actual origins of the name are open to interpretation and there are several theories: one theory is that it is from the Old English word haga, or Norman word hagi, which describe someone who lived near an enclosure; there is evidence to support 12th–13th century evolution from de Haga to de la Hagh to le Hawe, and finally just Hawe or Hawes. It is worth noting that Haga is one of the names identified in Anthony Camp’s book, My Ancestors Came with the Conqueror.

References to the Hawys / Hawes family can be found in the earliest surviving documents of Walsham. In particular, the Walsham Manor court rolls provide an amazing amount of detail about the family from the 14th century. Starting with Robert Hawys, who is identified in the court rolls and who would have been born around the year 1260, the family fortunes can be followed through the ensuing years all the way to my great-grandfather, George Hawes, who emigrated from Walsham le Willows before 1865 to start a new life in my birth place, Nova Scotia, Canada.

Life in 14th and 15th century Walsham was one of subservience to the lord of the manor who owned the land, granting varying amounts to tenants, or villeins, to provide for their families. Some villeins were wealthy and some were paupers. Every aspect of village life came under the direct control of the lord, and every few weeks, villeins were required to attend the manor court, probably held in the hall or manor house. Villeins were required to compensate the lord every time they acquired land, sought permission to marry, left the village to live elsewhere, and were often required to bequeath him their best beast when they died. Villeins paid fines for allowing their buildings to fall into a state of disrepair, but they were also fined for digging pits on the common to obtain the necessary clay to make the required repairs! They were regularly fined for trespassing and damaging the lord’s crops, for ploughing beyond their strips, for blocking up the village stream, and for “… failing in their services to the lord …”

The various entries in the manor court rolls, and subsequent probate records, suggest that the Hawys / Hawes family of Walsham was one of means, a situation which persisted up until approximately the time of the Civil War of the mid-1600’s, after which the family fortunes took a definite downward turn. Using the manor court rolls along with various other sources of the time, such as the Poll Tax of 1283, Lay Subsidy Tax of 1327, and the record of 1349 plague deaths in Walsham, one can piece together a fairly accurate picture of Robert Hawys and his immediate family:

The Poll Tax record for the year 1283 lists Robert’s assets as “… wheat, barley, oats, peas, one horse, one colt, one bull, two calves, three pigs, three sheep, and two lambs …”, with a total assessed value of 4.10s. Based on this assessment of his property, Robert was required to pay the “Hundred of Blackbourne” Poll Tax of 3s 5d, which was based on a tax “… of one thirtieth …” of his assessment. In the return of 1283, Robert, whom I have deduced to have been my 18th-great-grandfather, was near the bottom of the list, so while he may not have been the richest person in the area, he was certainly wealthy enough to have been taxed. The Blackbourne Hundred, which included Walsham, refers to a division of land detailed in the Domesday Book of 1086 and which was named after a local river. From these sources we learn that Robert had six sons and a daughter. He is assumed to have died by the year 1338, when Walter Hawys, who is thought to have been Robert’s oldest son, gave up his share of the family tenement to his younger brother, William, except for the “… bakehouse …”, to which he would continue to have access. It is interesting to note that the court rolls record that an unidentified individual was brought before the court in 1345, charged with stealing from the bakehouse; the outcome of the charge is unknown, but any resulting punishment would certainly have been severe by today’s standards. Walter died in 1349, a victim of the plague which swept through Walsham in that year; he would have been about 59 years old at the time. As was the custom, Walter’s estate was required to make a bequest of “… one cow …” to the lord of the manor; his tenement he bequeathed to his son, John.

Walter’s brother, William, was my 17th-great-grandfather. In 1327, he paid a Lay Subsidy Tax of 4s and his wife, Mansilla (or Milicent), was also required to pay a tax of 3s; both were identified as being “… of Finningham Rd …” That same year, 1327, William was probably granted the illustrated Coat of Arms, if one is to believe the East Anglian Pedigrees edited by Arthur Campling. In 1349, William also succumbed to the plague. Again as was the custom, William’s estate was required to make a bequest of one working-horse, or “… stot …” to the lord of the manor. William, who had two sons and two daughters, left his “… messuage …” (dwelling and out-buildings) plus 40 acres of land to his son, Robert, who was assumed to have been the eldest son. However, Robert apparently died very shortly after his father, and the inheritance passed to the second son, 16th-great-grandfather John Hawys. However, the actual succession is somewhat confusing since John also died in the plague of 1349; just how close the deaths were to each other is unknown.

Looking at the idyllic beauty of Walsham le Willows today, it is difficult to imagine the deplorable sanitary conditions of the time which allowed pestilence and disease to sweep the land with such deadly results. Of a village population of 800–1000, over 100 Walsham villeins are recorded as having died in the plague, or Black Death, of 1349. No doubt, about 100 women, and even more children also perished.. While the full impact of the plague on the Hawys family is not known, the records show that of Robert’s seven children, at least five were dead by the year 1349, three of those due to the plague.

While Robert and John shared the same fate in 1349, they had earlier married into the same family, the wealthy de Cranmere’s, who are assumed to have been associated with the area around Cranmer Green. John and his wife, Hillary de Cranmere, are known to have had two sons, William and Robert. In his will, John left his tenement to both sons, as well as the traditional “… one cow …” to the lord of the manor. William and Robert, born sometime before 1349, both lived to be adults and had their own families. At one time or another, they were both reeves of the manor, in charge of seeing that the peasants did their appointed work on the land. The appointment of reeve was apparently on a rotational basis among the more responsible tenants. William’s wife has not been identified, but William, who died in 1408, is thought to have had one son, 14th-great-grandfather William Hawys, born in Walsham about 1405. Connecting this William to the family described so far is somewhat conjectural, however, the manor court rolls, pedigree and visitation records, support the idea that subsequent generations are descended directly from this William and his wife, Isobel.

William and Isobel had four known children and with them, we are introduced to the Hawys preoccupation with the name “John”, given in this instance to both sons. Certainly, family research often leads to more than one offspring with the same name, however, it is usually a situation arising from the death of children with subsequent new-borns given the same name until a “survivor” emerges. In the case of William and Isobel, however, both Johns attained adulthood and raised families of their own. The complications of such a practice were at least recognized in the various records by uniquely identifying each individual. In this case, the eldest son, John, was generally referred to as John the Senior, or John the Elder. The junior John was understandably called John the Younger, but was also referred to as John of Weston; the reference to Weston may actually have meant Market Weston, a village about four miles north of Walsham, and as such would be the first indication of any members of the family moving from the actual confines of Walsham. William’s will of 1469, the first found for any member of the family, names Isobel and the eldest John as co-executors and requests that he “… be buried within the bounds of the churchyard of Walsham …” . Of course, William was not the first to be buried in the churchyard: there was a church on this site at the time of the Domesday survey of 1086 and generations of Walsham residents have been buried there for hundreds of years. The oldest surviving gravestone in the churchyard is dated 1684, and the only surviving Hawes gravestone dates from 1848. The transcript of William’s will is one of 29 Hawys / Hawes will transcripts that I have, covering the more than 200 year period 1469–1683, and which have proven to be most useful in providing an insight into the family history.

My ancestral line continues from John the Elder. Virtually nothing is known about this John during his lifetime, and his wife has not been identified, however, he is known to have had three sons.

John’s will of 1504 contains numerous bequests to family members including nieces and nephews, the children of his brother, John the Younger, and his sister, Katherine. As such, this will was quite useful in expanding on the information available on this generation of the family.

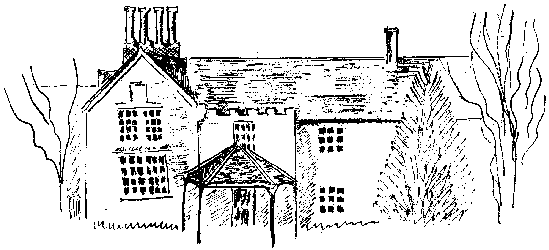

One of John’s three sons was 12th-great-grandfather, John Hawys of West St, who married Katherine Homlmes in Walsham about 1491. They had a large family of 12 children, eight sons and four daughters, and naturally, three of the sons were named John, and all lived to be married adults! John was a farmer who had a house and farm in West St, which property is still in use today as a working farm known as Home Farm. When I visited Walsham le Willows in 1995, the house was being restored by the owners, Mr and Mrs Smith. The building is timber-framed with a fully hipped thatched roof with a decorated ridge; it is one story and originally had an open hall, and also has an attic which contains bedrooms – the “restoration-in-progress” that I was shown, was nothing short of magnificent! The adjacent barns are very old with fascinating old timber framing. John also had the use of other land within the village, and in his will he left Angrave Close, to one of his sons named John, and Fishpond Close to his son, Stephen; apparently both named sons were under 24 years of age at the time. John was approximately 58 years of age when he died in 1528, shortly before his wife, who was made the executrix of his will. To his children, another John, Kateryne, Olyve and Isabell, he left one milk cow each. John obviously had more land-holdings than the two closes mentioned, since his will bequeaths “… all other lands, woods and pastures …” to his wife, Katherine. After her death, it is assumed that the Home Farm property was passed down to their son, John, who also became known as John Hawys of West St, but was apparently also called John Hawys of Cranmer. A second son was known as John Hawys of Weston, and it is interesting to note that at least two of this John’s sons took up residence in Ipswich, and it was this branch of the family which was to establish a land claim against the West St property, probably around 1600. As well, John of Weston’s descendants spread to London where, some of them at least, penetrated the higher levels of society, by marrying into titled families: Lawrence Hawes of London, Gentleman, married Ursula, the sister of Sir William Herrick, and in 1664, one John Hawes of London and Goldsmith was appointed Treasurer of Christ Hospital. On the other hand, this same London branch records that one Andrew Hawys of London, Fishmonger, took as his third wife, Mary Bloyre, who was simply identified as the daughter of “… a Frenchman… “!

The third son of John of West St to be named John was actually the first-born, and appropriately named John Hawys the Eldest. At this point, the role of 11th-great-grandfather has to be shared between John the Eldest and his brother, Stephen. Dealing with Stephen first, he married Marion Rookwood, and they had 10 children. Stephen, who had been left land by his father’s will and a “… featherbed …” by his mother’s will, obviously had considerable land-holdings in Walsham, and in 1524, he was required to pay a Lay Subsidy of 1s 6d based on his holdings. The full extent of his holdings becomes more obvious when he died in 1549, at the approximate age of 43, making numerous land-bequests in his will, including Stanton Close and Little Reeding Close to two of his sons. Besides bequests of money to his other children, he provided for Marion by leaving her all of his lands and tenement in Palmer St, as well as Spylman’s Close and Stony Land for “… the term of her natural life …”. Additionally, he required Marion to pay to each of their children, one cow at the time of marriage or moving out of the family home. Stephen’s daughter, Catherine, married John Vincent and they became one set of 10th-great-grandparents. One of Stephen’s sons, Robert, became the progenitor of the Norwich and Wymondham branch of the family in Norfolk which produced some notable scholars in the 1600’s, such as two generations of John Hawys of Norwich, Doctor of Physick. This branch of the family now skips two generations before “re-connecting”, so we will leave it at this point.

Returning to John the Eldest, my “other” 11th-great-grandfather, he has also been identified as John of Church St, and John the Tailor, which does little to help the task of keeping track of so many “Johns”! In any case, this John married Joan Gardiner, and they were recorded as having a family of four children, but this time there was only one son and one opportunity to name an offspring “John” ! Like his brother, Stephen, John had considerable land holdings in Walsham, which included the following parcels: Sares Acre, Hatchmere, Botoluysdale, Hulkys Close, Stronyclose, and the Syke. John died in 1529, only two years after his father, at the relatively young age of about 37 years. His will, in which he is referred to as “… John Hawys of Walsham the Taylour …”, was quite complex and he named many beneficiaries, and made many bequests. He remembered the churches in Walsham and Wattisfield, as well as Christ Church in Norwich, although the “Norwich-connection” is not explained in any documents that I have seen. He also remembered “… the pore peopill in the towne of Walsham …” with a bequest of 20s for the next 12 years. To his wife, Joan, he left his “… tenement and crofts …” for as long as she remained a widow and unmarried. In the event that Joan should remarry, John directed his executors to rent his lands and pay her 20s per year until a total of 20 marks was attained, a mark being defined as “… a measure of solver, generally eight onces, accepted throughout Western Europe …”, and worth about 2/3 of a pound. After this, or in the event that Joan should die first, he directed that his executors should take charge of his lands until his son, 10th-great-grandfather, John “in the Bushes” Hawys, who would have only been a small boy at the time, attained the age of 26. He dispersed his land holdings through several bequests and also directed the sale of his “… northern bullocks …”, with the proceeds to go to the payment of his various money-bequests. He also made bequests of some of his personal possessions, such as: coverlet, candlestick, and pewter plate to his eldest daughter, Katherine, and a second set of the same items to his son, John. It would be interesting to know if any such items have survived to the present day, and if so, where they are.

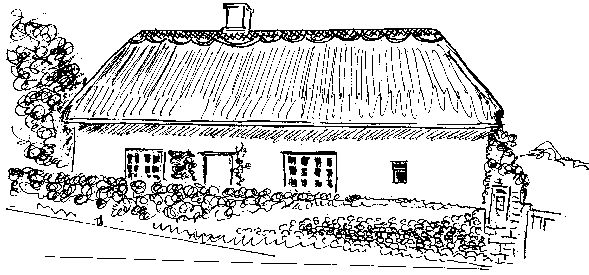

Although it is difficult to trace the actual ownership of properties such as the previously mentioned Rookery on Finningham Road, it appears that John “in the Bushes” grew up to occupy this property and raise his family there. As to why he was referred to as “in the Bushes”, one can only assume that it had to do with the lush foliage around the Rookery, which is still evident today. It was not likely for the reason facetiously suggested by my daughter, to the effect, that John may have been the village “peeping Tom”! From 1539, the Walsham parish register becomes available as a most useful source in sorting out and detailing the various Hawes family relationships. We only know the wife of John “in the Bushes” as Emme, however, sources suggest that they had eight children born between 1542–1564, five sons and three daughters.

The Lay Subsidy of 1568 records that John had to pay a subsidy of 5s, based on his land-holdings, valued at four pounds. John would have been about 56 years old in 1577, the year that Sir Nicholas Bacon commissioned a survey of the manor. The survey was no doubt inspired by the desire to insure the utilization of the land which would produce the greatest profit, and the results are detailed in The Field Book of Walsham le Willows. Of the approximately 95 tenants identified, eight were members of the Hawys / Hawes family, including John “in the Bushes” and his eldest son, Andrew “the Elder” Hawys. John made his will on May 20th, 1581, dying sometime before probate a year later when he would have been about 60 years old. In his will, he left the close in Wattisfield called Strondeswood (mentioned earlier) firstly to Emme, and then to his son, John, after her death. In the 15th century, Strondeswood was situated north of the Rookery on the parish boundary with Wattisfield. It is interesting to note that John’s will makes no mention of the Rookery property as such, and it is possible that he may not have even owned it at the time of his will. John also made money bequests to named children Francis, Andrew, Philip and Thomazine. Emme also inherited “… all moveable goods and cattell …”. His will also contained a provision for monies to help the parish poor each year at Christmas and Lent until a total of 20s was paid.. Emme lived on for another 24 years dying in Walsham in 1605: she would have been about 82 years old, quite an exceptional age for the time.

A few years after the death of John “in the Bushes”, the family of John’s first cousin, James Hawes, became embroiled in a manor scandal involving charges of “… lewd practices …”, … however, this seems like an appropriate subject to leave for the next instalment.

James McNeill

What the Papers Said

It was reported in the Bury Post dated 26 January 1791 that Jonathan Smith junior of Walsham le Willows was committed to jail, charged with having, on the 18th of this instant, maliciously and feloniously wounded and hamstrung a cow, the property of Joseph Abbott of Stanton.

The Bury Post on the 20th April 1791 carried an advertisement for Thomas Walnes general stores in Walsham: “True Daffy’s Elixir – a most excellent and well known and genuine medicine faithfully prepared for up to 60 years. For the cure of stone, gravel, ulcerated kidney, the gout, rheumatism, cholic, dropsy, scurvy, surfeits, convulsions, disorders peculiar to women, consumptions, the piles, fevers and the spitting of blood. True Daffy’s Elixir is sold wholesale and retail in bottles of 8oz. For 1s 6d (duty included)”

In the issue dated 22nd April 1795, Robert Tricker of Walsham placed a for sale notice for “… a stack of exceedingly good upland hay containing about 15 tons of the year 1793”

The Post on the 1st July 1795 carried an auction notice: “To be sold by auction at the Swan, Walsham le Willows, an exceedingly well timbered house and premises with a large yard and garden, well planted with choice fruit trees in Walsham aforesaid, now in several occupations of John Morley, William Turner, the widow Flynn and Marcy Rich. The purchaser may have full possession on 10th October. On the same day will be sold at auction a complete set of brewing utensils for the brewing of three combs of malt, with a large quantity of exceedingly good iron bound beer casks, also pipes, hogsheads, half hogsheads and barrels together with about £50 worth of valuable household furniture consisting of a mahogany double chest of drawers, bureaus, chairs, pier and other glasses and other articles.”

On 23rd November 1796 another auction was reported to take place in Walsham, this time at the dwelling house of Sam Drake, plumber and glazier. “All the household furniture consisting of four exceedingly good feather beds, two of which are mahogany post, almost new 8 day clock in mahogany case, two mahogany bureaus, mahogany chairs and tables, brewing utensils and sundry other articles. All expressed in catalogues to be had in due time at the Boar in Walsham and most public houses in the neighbourhood.”

The Post 15th February 1797 – “Whereas on Monday 30th January 1797 between the hours of 10 and 11 o’clock in the forenoon, some evil disposed person or persons wounded a colt, the said wound being 10 inches long and 4 inches deep, on the premises of Thomas Thompson of Walsham le Willows. Whoever will give information of the offender will receive 5 guineas reward by me, Thomas Thompson.”

The Bury Post dated 2nd August 1797 reported that: “On Thursday night or early Friday morning a chestnut cart mare was taken out of the pasture of Mr. Thomas Diggens. The mare, six years old and 14 hands high, with a full mane and tail, a white shim down her face, a small callous on her near fore leg proceeding from a kick and a white mark behind occasioned by the crupper. Upon conviction, a reward of 5 guineas will be paid. If the said mare be rode away with and turned off, any person conveying her as above shall be handsomely rewarded for their trouble.”

The issue of 21st March 1798 reported: “At the Boar in Walsham to be sold at auction two lots. Lot 1 – an acre of rich meadow land lying in the meadows called Lammas in Walsham aforesaid. Lot 2 –two dwelling houses situated in a street called Clay Street in Walsham with an orchard and about one acre of rich land to the same, now in several occupations of John Frost and Thomas Mowle. The premises are copyhold to the manor of Walsham aforesaid.”

James Turner

Note:

During this period animal maiming was rife. It was considered a form of protest, together with rick-burning, by the poor against the wealthy. Jonathan Smith was fortunate not to have been transported. The Police Service had yet to be formed and offering large rewards was probably the only way the culprit could be traced. Huge rewards, at a time when most people were barely eking out a living must have led to gross miscarriages of justice.

The Lammas Meadow, or Mickle or Great Meadow was at West Street behind Home Farm. Tenants had small strips of the meadow to provide hay for winter feed which had to be cut by August 1st, Lammas Day, because animals were then allowed to graze there.