The National School in Walsham-le-Willows

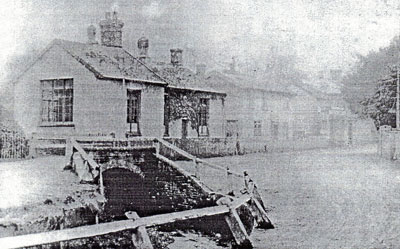

One of the recurring features of the East Anglian lanscape is the village school. So often it was a rather impressive building constructed of good quality brick, or in some places knapped flint, with high arched windows picked out in limestone. The roof is at a fashionably high angle and covered in finely trimmed slates; it may be decorated with carved bargeboards, turned finials and possibly a small tower or turret containing the school bell. Surrounding the building is an ample plot, now covered with asphalt, and bounded with metal railings. Some, such as those at Haughley or Old Newton, still fulfil their original function, while others, such as Wattisfield, Hepworth or Finningham, have been converted into rather desirable private houses. This is not the picture in Washam le Willows. We have a rather mundane “School House”, a joiner’s workshop, a gap in the wall and glimpses of a part brick and part flint structure on the other side of the river; further up, across the road, is the more conventional Infants School.

The Origins of The National School

The National Society for Religious Education (Church of England) formerly known as the National Society for Promoting the Education of the Poor in the Principles of the Established Church, was founded in 1811. Its aims were to encourage the spread of education and in particular to provide a supply of teachers trained to use the monitorial system, and to offer grants to assist with the building of schools. Early on it sought to establish committees in dioceses (precursors of Diocesan Boards of Education) and these became important instruments of development. The National Society received a letter of April 3rd 1832 signed by the Bishop of Norwich, asking about building a school in Walsham, then his diocese. The letter included an application to become a National School and to receive a building grant.

The school was built in 1832 at a cost of £125. It consisted of one single-storeyed room measuring 32ft by 20ft with a maximum ceiling height of 11ft. It was constructed of red brick with a floor of white lump brick and a roof of countess slate.

There were two windows to the north and two to the south. Fittings included one desk (ie the teacher’s), 100ft of forms, and a fire-stove at the west end of the room.

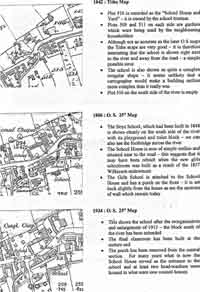

The land had “belonged to the parishioners by whom it was given”, and costs included £2 . 14s. in legal fees for the transference of ownership to the trustees of the school. In 1837,in response to many enquiries, the National Society published a booklet giving advice about the construction and the arrangement of school-rooms; it included 10 case-studies of recently constructed schools from various parts of the country, and amongst these was the new school-room at Walsham. When the Tithe Map was drawn in 1842 there was a “school house and yard” owned by the School Trustees in a position roughly equivalent to that of the present School House, and the 1841 census showed that the 28 year-old schoolmistress, Susan Kent, was living in that house. White’s 1844 Directory confirms “a school supported by subscription, except payment of 1d per week by each student”.

An application dated 6th April 1847 was sent to the National Society concerning the building of a new Boys School, with the original building retained for girls. Land to the south of the river was conveyed to the Archdeacon of Sudbury in 1848 and a grant was awarded for the building of a new school-room 30ft long, 18ft wide, 11ft 6in. high. This remains as the flint section of the building on the far side of the stream. The Society recommended a space of 7 sq ft., sometimes reduced to 6 sq ft. for each child, so the new building could have housed 80 or 90 pupils. White’s 1855 Directory says the “National School is a commodious building attended by about 50 boys”. The girls Subscription School had 90 scholars.

Education in Victorian Walsham

On 10th October 1848 William Egmont Young takes up his duties as Head of the Boys School. He was a young man, (born 22nd July 1823), who had trained at Westminster from 1846 to 1848 and had previously gained experience teaching in private schools. His appointment marks the beginning of a period of great stability in the boys school running through 37 years to his eventual departure in 1885. The girls and infants departments were similarly very settled; we know that in 1855 Miss Rhoda Bridges is mistress of the girls school and Miss Firman is responsible for infants; both are still there in 1864, and each probably served the village for about twenty years or more. In view of the very large numbers of children involved the pressure in terms of work and crowding must have been enormous, although attendance rates were often quite low by today’s standards and there were invariably young teaching assistants such as “Ann Burwood – aged 15 – schoolmistress” (1851 census), to help. Classes were almost certainly organised on the so-called “monitorail” teaching system where older students learned their lessons from teachers and then passed this on to the younger children. The “monitors” might well become the young “schoolmistresses”, and having served a sort of apprenticeship then go on to complete formal teacher training at a college.

The pressure in the girls and infant school was relieved through substantial financial investment from the Wilkinson family. They were major landowners in the parish and we are told that “the girls and infant school are endowed by Captain T.H. Wilkinson” (Morris Directory 1868), and that ” the girls school was endowed by the late Miss D. Wilkinson in 1857″ (Kelly’s Directory). This allowed expansion and a new school room was built in the centre of the plot next to the street; this was largely demolished after the school closed in 1965 and all that remains is a section of wall on each side of the present-day driveway. It is quite probable that the original schoolhouse was remodelled or possibly completely rebuilt at the same time. There is a wooden plaque, now hanging in the joinery workshop, which commemorates the 1857 endowment to “Walsham Girls School”; it lists the seven trustees who include four members of the Wilkinson Family and John Martineau. This plaque carries the date 1872 and may well represent the trustees confirming their independence from the newly opened Infants School; henceforth the infants would no longer be educated with the older boys and girls.

Financing schools in the middle of the nineteenth century could be difficult. Subscriptions from wealthy landowners, clergy and businessmen were common, but so was the “payment of one penny per week by each student”. By 1870 the boys school was using a more refined systerm: the sons of labourers were paying 1d per week, sons of small tradesmen paid 2p, sons of farmers paid 3p and boys from outside the parish paid 6d. The reputation of the school must have been very good because there appear to be 15 boys in the last category. By the 1860s the school is getting some financial support from the Townland charity and by 1892 “the town estate” is contributing £15 per annum. In 1870 we had the first of the great education acts – the Elementary Education Act (sometimes called the Forster Act), which recognised that voluntary schools for the poor could not alone satisfy the national needs, and laid the foundations of the modern state education system. White’s Directory of 1874 mentions the existence of government grants and these must have become a regular feature once elementary education had been made compulsary in 1880.

The reasons behind the establishment of education for the poor were no doubt numerous. Throughout the Victorian period there was a growing philanthropic tide, but this ran alongside benevolent paternalism and in some cases evangelism. Some people thought that limited schooling might help control a potentially unruly population; others thought that it was essential to educate youngsters to cope with increasingly complex technology. In rural communities there must have been thoughts about maintaining a well-trained and compliant workforce. Elizabeth Wilkinson (b. 1834) left a legacy to the girls school, which was to be used to set the girls up for “service in a big house” when they left school. This was spent in buying girls a tin trunk with some of the basic requirements such as caps and aprons; in later years this was changed to the choice of a workbox or a writing case. When Elizabeth Gapp died in1891 at the age of 82 she left £100 to John Martineau “to be invested and held by him upon trust and the interest from it to be distributed in prizes of money or books or clothing as he shall think fit for the children of the girls school who have passed three subjects at the annual examinations”. These prizes were distributed every few years and in 1914, 1916 and 1919 the money was being spent on bags, scissor cases, writing cases and baskets – all very appropriate for any girl who was going into service: by the 1960s the prizes were given in the form of books.

Despite this drive to educate the poor we are left with a feeling that real work was more important. The school calendar was of coarse built around harvest time and the need to get every pair of hands possible into the fields at that time of year. The frequently low attendance rates related partly to illnerss, epidemics and bad weather, but also to the need for someone to scare birds from newly sown crops, pick stones, supervise livestock or help with the hay. This also explains why the number of boys attending school was frequently much lower than the number of girls. Throughout the nineteenth century most Walsham children would have started work by the age of 14 and many by 12. The 1871 census has surprising statistics concerning schoolchildren in this village, who regardless of age, are described as as “scholars”. Children aged three attended school, with 8 boys and 10 girls in this category. Then at four there are 19 boys, 8 girls. At the age of 12 the numbers change dramatically, with only 2 boys, 13 girls. The decline continues, with, at thirteen years, 3 boys, 9 girls. At fourteen the numbers have dwindled to 2 boys, 1 girl, and at fifteen there are no boys at all, and only 2 girls. The same census also shows 2 eight-year-olds working as “bird keepers on fields”, a nine-year-old “bricklayers boy”, a nine-year-old farm labourer, and ten-year-olds recorded as a scullery maid, an errand boy, a bird keeper and an agricultural labourer.

Richard Belson

To be continued in the next issue. The Start of the Twentieth Century