Walsham Hall

The hall that this article is about is not the original medieval hall which in 1577 was described as being decayed and no trace remaining. The medieval hall is thought to have been close by on what was known as Hall Green.

The second Walsham Hall was up the Summer Road and stood exactly on the same spot where the classical styled house known as Willow Court is now. Walsham Hall was built of red brick with a slate roof; the same type of brick can be seen on the existing wall which surrounded part of the grounds along the Summer Road and the Ixworth Road. It is not known when the hall was built; a building is marked there on the 1817 tithe map. A John Hooper Wilkinson bought some land in Walsham from Rebbeca Lloyd of Lancing in Sussex, in 1828.

He is mentioned in the 1841 census as living at that site. It is open to conjecture exactly when the hall was built, probably in the early 19th century.

There were a number of different owners during the lifetime of the hall including a Baron, a Baronet, two Army Officers, and two Bishops.

When John Cooper Wilkinson died in June 1883, and his wife in the following year also in June, the hall passed to his son Thomas.

Thomas by this time was married and was the Anglican Bishop for Northern Europe. Before that at the age of 33 he was the Bishop of Zululand. He sold the hall and the grounds to the Church of England for£2,000 They intended to use it as a home for children. He then gave in 1889 another 37 acres to the Church. With this extra land bringing the total up to about 95 acres they decided to run it as a farm home for boys.

After making some alterations and building workshps, the home opened in 1896 and accommodated forty boys aged from 10 to 16 years. The home was registered as an industrial home by the government and was subject to inspections. It was often marked on maps as an Industrial Home for Waifs and Strays; the name used by the Church was Walsham Farm Home. A number of the boys there were sent by magisrates (mainly from London) for some minor crime or because they were found to be in need of care. In 1896 the home received three shillings and sixpence a week from the Government for each boy sent there.

One type of boy sent there is as follows. We shall refer to him as boy A, boy A appeared before Marylebone Magistrates as he was found wandering and not having any home or guardian.

One type of boy sent there is as follows. We shall refer to him as boy A, boy A appeared before Marylebone Magistrates as he was found wandering and not having any home or guardian.

His mother was a prostitute and the boy was illegitimate, the court ordered that he be sent to Walsham to be detained there until he shall attain the age of 16. In October 1901 when the boy was 16 he was sent with the consent of his mother to the Army recruiting office in Bury St Edmunds. There he was enlisted as a band boy in the 4th battalion Rifle Brigade stationed in Dublin. The Army was a popular place to send boys; another was to send them to Canada. In an Inspector’s report of the home in 1906 it was noted as “Disposal of children, five less than last year, 4 went to Canada, a fifth went into a motor factory.” In 1884 a government report stated that 2,108 boys and 133 girls were sent to the colonies from institutions in England.

The home was neither a prison nor a reformatory, although the boys had to stop there until they were 16. Undoubtedly the discipline there was strict, bearing in mind there were forty boys from disturbed backgrounds at the home. Corporal punishment was administered at times, each occasion being recorded in a book. A few boys also absconded but were soon returned to the home.

The home was neither a prison nor a reformatory, although the boys had to stop there until they were 16. Undoubtedly the discipline there was strict, bearing in mind there were forty boys from disturbed backgrounds at the home. Corporal punishment was administered at times, each occasion being recorded in a book. A few boys also absconded but were soon returned to the home.

Walsham Hall was run as a farm, the boys with some adult help cultivated the fields, some of the produce was used in the home, and the surplus was sent to Bury market. In addition to working on the farm the boys received tuition in the three Rs together with carpentry and other skills. They had a football team and a cricket team, and also attended church. Each boy had three suits of clothes, a best suit of blue cloth, a second one of grey cloth and a corduroy suit for working in.

It was exceptional for any boy to have so many suits in those days. They also received medical and dental treatment when necessary. On the whole they were looked after very well compared with the background they came from. After several years of successful work the governments approach to commiting children to homes such as this changed. Partly to save money and also to use a more humane method, children were more often put on probation. Coupled to the fact that the government insisted on more theoretical work such as growing peaches in hot houses, it became obvious that the home could not continue in this manner.

The home was originally intended to be run as a farm and could not cope with this change, there were many vacancies at the home so it became uneconomical to maintain. In 1921 it was reluctantly decided that Walsham Home Farm must close, and so ended what was arguably the most important period in the Hall/s history.

After the closure of the home, Walsham Hall was bought by a Major Fasithful, who ran it as a progressive school. Little is known about the curriculum at the school, but it was probably based on the principles of the well known progressive Summerhill School, which had opened at Leiston a few years earlier.

It was sold next to Baron von Wick (pronounced Vick) who was said to be a race horse owner; he sold the hall in 1931.

The next owner of the hall was Bishop Maxwell-Gumbleton, the Suffragan Bishop of Dunwich who lived there from 1931 to 1936. He was by some accounts an eccentric character. To give him his full name he was the Right Reverend Maxwell Homfray Maxwell-Gumblrton. In 1916 by royal licence he assumed the name and arms of Maxwell-Gumbleton, an Irish family to which he was distantly connected. In addition to being the Bishop of Dunwich he was also the rector of Hitcham near Stowmarket. He had a Bishop,s throne made and installed in the chancel of the Church for his use.

The owners after him were Major and Mrs Whatman. He was a retired army officer and a director of Mann Egerton in Norwich. On Major Whatman’s death in 1965 his wife sold the contents of the hall and moved to an apartment in London to be nmear her daughter.

The last owner of the hall was Sir Nicholas Cayzer Bt (later Lord Cayzer) of the Grove, who had the hall demolished. In its place in 1968 he had built two houses designed by the classical architect Raymond Erith, Willow Court and Willows House. Willows House stands at what was the entrance drive to Walsham Hall.

The history of the hall would not be complete with out mentioning the game place, an open air theatre from medieval times which stood in the grounds of the hall; it was still mentioned in the early 20th century as being there. The following is a 1577 description of it:

Walsham Towne The sayd Game Place in the tenure of divers men to the use and behofe of the towne of Walsham aforesaid is a customary ground holden of the manor of Walsham and a place compassed rownd with a fayer banke sett with? cast up ona good height and havinge many great trees called populers growynge about the same banke, in the myddest of the earth with a stone wall about the same to the height of the earth made of purpose for the use of stages playes.

Wouldn’t it be nice if Channel 4’s Time Team came and found the site for us?

I am indebted to the following for their help

- Church of England Children’s Society

- Mary Wall. Missing Ancestors

- Audrey McLaughlin

- Susan Williamson

References

- S.R.O.Cayzer baronets of Roffey Park Sussex

- Walsham Hall deeds 1803/10

- S.R.O. part contents Walsham Hall Sale

- HD 1180/72

- The Field Book of Walsham le Willows, edited by Kenneth M. Dodd

John Champion

100 Years Ago

Old Age Pensions

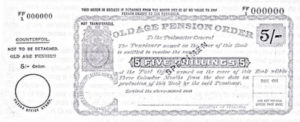

On the first of January 1909 the Old Age Pension Act came into being. Every man and woman who had reached the age of 70 years, and whose means of support did not amount to more than £26 annually, received a pension that varied between 1 shilling and 5 shillings a week depending on income. Initially the pension, which was paid through the Post Office, was not available to those claiming parish relief. However, many stopped claiming relief and applied for a pension, not only as the 5 shillings was often more than the relief, but being a pensioner did not carry the same stigma as being a pauper.

Pension Officers would visit claimants to check on their income and character, assessing whether their applications were genuine. Pensions would normally be denied if you had been sent to prison in the previous 10 years, if you were habitually drunk, if you had never worked when able to do so, or were of bad character (what a good idea!). Sometimes the work of Pension Officers seemed to be dangerous. Information sourced from the Department of Work and Pensions shows that compensation was paid to officers after receiving dog and insect bites, as well as broken arms, legs and ribs. One officer fell through a trapdoor in a brewery, another caught fever whilst visiting an O.A.P, and one got brochial catarrh and debility resulting from immersion in a river.

The Bury Post in January 1909 reported: “in Walsham le Willows on Red Letter Day, 27 persons received their pensions from the village post office.” (the photograph below was taken in 1905). “The oldest inhabitant who is over 90 could not make it but has applied through signing authority. One very respected couple who have worked all their lives to bring up a large family are both pensioners. The husband is now losing his sight, thus the new pensions have come at a most opportune time. A pensioner, well over 80 years old, walked two miles to cllect his pension, when asked if he could walk back he replied “well of course I can.”

Information from the D.W.P shows that we now have more pensioners than children. We have an 84% chance of reaching pension age, whereas in 1909 it was 24%. In 1909 there were half a million pensioners, now there are 12 million. The 5 shillings (see order below) in 1909 could buy 5 large loaves of bread, half a pound of tea, 1lb of sugar, 1lb of cheese, 7lb of potatoes, 2lb of meat and 7 pints of milk. In today’s supermarket this would cost over £20.

In Walsham the Temperance Society arranged a tea and social gathering for the new “Old Age Pensioners” and all villagers over 70. About 90 sat down to good English fare and the joints of meat rapidly vanished, showing that in old age they had not lost their appetites. One gentleman hale and hearty was nearly 90, and several were well past 80.

Several pensioners gave amusing but sad tales of the days past when they went to work, of the pay they received, and the hardships they endured in what was termed “the good old days”.

Apples and oranges were distributed throughout the evening and there was a selection played on the gramaphone. The happy party dispersed with those living at a distance taken home in conveyances. Seven old people who could not attend due to sickness were presented with meat and bread at their homes.