Elizabeth de la Pole and Walsham

In 1460 Elizabeth Plantagenet, the daughter of the Duke of York, married John de la Pole, son of the late Duke of Suffolk. She was sixteen, a direct descendant of King Edward III. He was eighteen, his great-grandfather a merchant. His father, William de la Pole, was one on the most powerful men in England, and had been murdered in 1450. By contrast, John never sought the political limelight, even when invested with his father’s title in 1463. By this time Elizabeth’s father had also suffered a violent death, and her brother has seized control of the country, assuming the crown as Edward IV in March 1461, the month before his nineteenth birthday.

The de la Poles, based at Wingfield in this county, had held the manor of Walsham since at least 1441. After William’s murder the manor was inherited by his widow Alice. She was born Alice Chaucer, and her father Thomas is generally regarded as a son of the poet. Thomas, upwardly mobile, married the heiress of the Burghersh barony and acquired an estate at Ewelme in Oxfordshire. His daughter Alice preferred it to her Suffolk properties and died there aged seventy-one. Despite the arranged marriage of her son to a member of the York dynasty, she was a staunch Lancastrian. Nevertheless, the display of heraldry on Alice’s tomb in Ewelme church naturally includes her son’s shield incorporating the Yorkist arms of Elizabeth his wife.

Yorkist heraldry also appears at Walsham, as noted in this journal (August 1998), but a few comments can be added. The royal beasts on their late fifteenth century pedestals are superimposed on a tower which was documented as finished, presumably with the present battlements, before 1403. Each beast and pedestal, carved from a single block, is fixed to the earlier stonework by four metal rods sealed with lead, the sockets clearly visible. The only written record appears to be of about 1772 when John Ives described the beasts as ‘the Types of ye 4 Evangelists’, a mistake understandable on a viewing from ground level. To the northeast is the Clarence bull which could be taken for the emblem of St. Luke, while to the southeast is a creature something like an eagle for St John, and one of the Mortimer lions to the west could be mistaken for the lion of St Mark. The other lion was presumably so eroded, even then, that it did service for the winged man of St Matthew. Seen today, the lions lack their front legs, and the creature on the southeast has lost its right foreleg. This animal is a griffin, the lower part carved identically with the two lions, while the upper half is winged like an eagle. This majestic beast featured in royal heraldry from the 13th century, and was the particular emblem of Edward IV’s ancestor and namesake, Edward III. The royal griffin like the two white lions of Mortimer, remained as natural stone in statuary. The other beast, the Bull of Clarence, painted black in manuscripts, was so well known by its shape that it was also left uncoloured on external sites. The Tudors erected similar royal beasts at Windsor and Hampton Court, but these are now replaced by modern reconstructions, unlike Walsham’s 15th century originals.

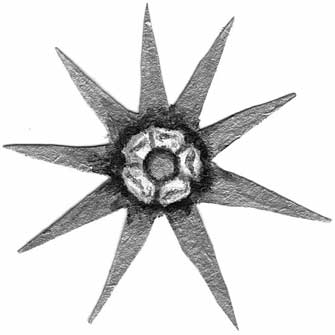

Inside the church the roof is adorned with devices known as ‘sunbursts’ and roses ‘en soleil’, favourite emblems of Edward IV, wrongly suggesting that the structure dates from his reign. Shadowy outlines of some of these decorations show that a few have dropped off the roof braces, indicating they are wooden cut-outs fixed to timbers erected many decades before. Apart from the roof decoration, a sunburst and at least two white roses appear in the medieval glass fragments of the east window, and of particular interest are the twisted vine borders on the circular rose panels. They are identical with the circular border at the top of the window which surrounds some apparently unusual lettering. This is however, simply normal Gothic script mistakenly reversed when assembled to form the present window in 1878. The inscription should read ‘deo’ and, accompanied by a lost roundel reading ‘laus’, would have spelt out ‘laus deo’: ‘praise be to God’. This phrase, with the vine-circled white roses, was part of the same scheme, a Yorkist display, There are also two painted glass panels at the lower corners of the tracery showing vines with leaves and grapes. These were emblems of Gascony, an English possession until 1451. The mysterious crimson hats (chaperones) held by heavenly hands in four of the other fragments suggest the Burgundian chivalric Order of the Golden Fleece. Edward IV donned such a hat when admitted to the Order on the marriage of his youngest sister Margaret to Charles Duke of Burgundy at Bruges in 1468. Edward’s shield, the lions of England quartered with the fleur de lys, is also shown in the window, like the inscription, mistakenly reversed.

In July 1475 Edward invaded France, hoping to reclaim English possessions such as Gascony. The five English dukes, including John de la Pole, accompanied the king on this prestigious enterprise, and he unwisely expected help from his Burgundian brother-in-law against their common enemy the French king Louis XI. After a month of minor skirmishes Louis agreed to pay a great deal into Edward’s exchequer, and so the adventure ended. It is probable that the whole Yorkist decoration at Walsham, pinnacles, roof ornaments and glass, refers to this campaign. The dating gives support to this theory, for dowager Duchess Alice died in 1475. With her Lancastrian sympathies she is unlikely to have authorized a Yorkist display, whereas with John as lord of Walsham manor, a show of support for a royal kinsman is more likely.

An undated letter from Elizabeth de la Pole survives in the Paston correspondence. Signing herself ‘yowr frend Elizabeth’ she asks ‘Mastyr Paston’ for temporary lodging, and concludes ‘I pray yow rekomaund me to my Lord Chamberlyn’. The Lord Chamberlain was William, Baron Hastings, Edward IV’s close companion throughout his reign, and naturally an adviser during the French campaign. In our window there is a prominent Hastings shield, showing a dark crimson sleeve, a medieval sign of office, on gold. Strictly speaking, William Hastings’ branch of the family bore this emblem in different colours, black on silver, but this mistake would be a result of the glazier’s ignorance of heraldry. Subsequently, on the king’s premature death in 1483, Hastings was beheaded at the order of Elizabeth’s younger brother, shortly to become Richard III.

Despite Richard’s evil reputation, largely the result of Tudor propaganda, he respected his sister. On the death at ten of his son in 1484, he named Elizabeth’s eldest son John, Earl of Lincoln, twenty-two years old, as heir to the throne. Lincoln was, of course, passed over on Henry Tudor’s usurpation in 1485, and ultimately he rebelled against the new dynasty. Leading a troop of Yorkist supporters and German mercenaries, he was killed by the Tudor army at the Battle of Stoke near Newark in 1487. The duke his father kept out of trouble and died a natural death in his fiftieth year in 1491. The Suffolk succession then passed to the second son, Edmund, demoted by Henry VII to an earldom and forbidden to leave the country lest he raise another foreign army like his brother. Edmund, with a better claim to the throne than the Tudors, was sent to the Tower in 1506. Still regarded as a threat, he was executed by the next king, Henry VIII, in 1513. The manor of Walsham had been formally passed by Henry VII to the Earl of Shrewsbury before 1509, so ending the de la Pole connection with this township. As for Elizabeth, she died in her fifty-ninth year in 1503, and is buried with her husband at Wingfield.

Their alabaster tomb against the north chancel wall shows John in armour, wearing his Garter insignia, while Elizabeth’s damaged effigy is hardly visible. She wears a coronet, veil, wimple and surcoat like most aristocratic widows from the fourteenth century onwards. John’s pillow is formed from the de la Pole crest of a Saracen’s head, and the double-tailed Burghersh lion is at his feet, but Elizabeth’s family heraldry is ignored. By 1503, it was dangerous for families with Plantagenet connections to display the royal arms when the Tudor’s claim to the throne was so tenuous, and several people of royal stock were executed by the Tudors on trumped-up charges, often involving heraldry. It might be wondered how the Yorkist display at Walsham was allowed to remain, but although the Tudors vilified Henry VII’s immediate predecessor, Richard , it was politic to honour Edward IV as he was the father of Henry’s queen, another Elizabeth Plantagenet, our Duchess of Suffolk’s niece.

Brian Turner

Principal works consulted

Clive M. This Sun of York 1973: Dodd K M (ed.) The Field Book of Walsham le Willows 1974: Gairdner J (ed.) The Paston Letters 1983: McLaughlin A. Some 15th Century Benefactors of St. Mary’s, Walsham 1994: Ross C. Edward IV 1974: The Wars of the Roses 1986: Stanford London H. The Queen’s Beasts 1954.

Walsham Gilds and Gildhall

Long before the days of the Whitsun processions held by the Temperance Society and Band of Hope, members of Walsham gilds held their annual parades – in the case of St. Katherine, on 25th November each year.

Medieval men and women had no choice when it came to belonging to a parish and/or a manor but membership of gilds was voluntary. Gild or geld means payment implying entry fees and subscriptions so membership was restricted to those who could afford to pay. Perhaps one fifth of the population belonged; in Walsham this would have been about 100 people.

Civic and trade or craft gilds were set up in towns partly to protect the rights of merchants and to solve problems caused by slumps in, for instance, weaving.

But village gilds were religious gilds run by local people for their benefit, membership giving them status in the village, and respectability. They celebrated the feast day of their particular saints by church attendance, meetings, feasts and processions. Anyone who has been on holiday in Spain, France or Italy in the week following Whitsun will have witnessed a Corpus Christi procession. The gild provided social benefits, supported members in their old age and sickness, paid for their funerals providing priests for prayers and masses – a medieval requirement.

Early wills often provide the only information regarding village gilds and show that Walsham had four. The earliest mention is in the will of Nicholas Smith who, in 1460, left 10s coming from the gilds of St. John the Baptist and St. Katherine (money he had paid in) for a trental ie. funeral masses. In 1465 John Swift bequeathed mass pence from the gilds of Holy Trinity, St. John the Baptist and St. Katherine to ‘the Friars Preachers and Augustinians of Thetford’ .

William Potenger, a chaplain of Walsham, in his will of 1481, asked to be buried before the altar of St. Katherine. Gilds often had side altars in church aisles where members worshipped and, if the south aisle in St. Mary’s church held St. Katherine’s altar, then the stone coffin there is that of William.

In 1489 Richard Day, who lived where Yew Tree Cottage now stands, made his will before going on a pilgrimage overseas. He left his ‘brass pan for 24 gallons’ to the gilds of Walsham – presumably to help prepare food for the large numbers attending the feasts.

Agnes Welles and Alice Terold also left money in their wills; women were not excluded.

Thomas Berne, in 1496, gave one rood of land (which became the Camping Close and later the Game Place) to the profit of the church and gild of St. Mary and other gilds in Walsham.

The town of Walsham held 10 acres of free land at West Street called St. Katherine’s Close (1509 Rental). The profits on this field would have gone to help maintain the gild.

In a manor court held in 1462 William Vincent was fined 3d for placing a hedge on the way leading from the church up to ‘le yeldhalle’. Lawrence Rainbird, in 1504, left the township of Walsham timber for a gildhall ‘if so be that they intend to make the hall’. The present building is provisionally dated by Leigh Alston at 1520 (he has yet to examine one of the three cottages) but it would seem there was an earlier gild building of some sort.

The upper floor of the gildhall was one long room to accommodate a large number of people for ceremonies, feasts etc. and was open to the roof displaying the attractive woodwork. It is possible that part of the lower floor was let out as living and commercial premises to raise money for the gilds; William Vincent was known as ‘at the Gildhall’ – a form of recognition, there being several William Vincents in the village at that time. But the Lay Subsidy of 1524 refers to the stock of two gilds so perhaps both floors were used by gilds.

The religious and social activities came to an abrupt halt in 1547 when Henry VIII closed the monasteries and other religious institutions; this must have had a devastating effect on the gild members. Fortunately the gildhall in Walsham was preserved by the village and is now owned and cared for by the Old Town Trust.

Audrey McLaughlin

This article is based largely on and inspired by a talk by David Dymond at the Suffolk Historic Buildings Group Day School on Guildhalls held on 28th May 2000. Peter Northeast translated the early wills.

Walsham le Willows (Brass) Temperance Band

‘We beg to draw your attention to the above Band, and to say that we shall be pleased to serve your interests during the coming season in attendance at GARDEN PARTIES, SPORTS, FLOWER SHOWS, GALAS, FETES etc.

We have a good variety of Music, including Selections, Marches, Dances etc. We should at all times do our best to meet your requirements in every particular.

The Band provides its own Gas Light, to facilitate playing on grounds after dark, when required. For particulars as to terms, apply to either of the following: Wilfrid Y Nunn, Band Master – Harry W Hubbard, Hon. Secretary.’

Thinking about the difficulty the Millennium Committee have had in acquiring a band for the 2000 Carnival brought this (undated) advertisement to mind.

What the Papers Said

A continuation of articles written about Walsham le Willows in the Bury Post.

19th August 1810 – The Bury Post reported that:

‘From the suddenness of the thaw after the severe frost on Wednesday night, John Borham, a Walsham postman, in returning home from his rounds, slipped down and broke his leg, by which unfortunate accident it is feared he will never be able to resume his occupation again’. A later report stated that he had died as a result of the accident.

On 10th July 1811 notice was printed of a house to be let:

‘A convenient dwelling house situated in the churchyard at Walsham le Willows, consisting of a parlour, keeping room, kitchen, three sleeping rooms, cellar, store room and a large garden walled round, with fruit trees. For many years in the occupation of Mrs Elizabeth Catchpole, deceased, and is a good situation for a private family. Walsham is a large and pleasant village situated 11 miles from Bury St. Edmunds and like distances from Stowmarket, Diss, Thetford and Eye. There is a regular post three times a week and coaches pass daily’ [Elizabeth Catchpole had died in May 1811 aged 69 years]

The following year on 6th May 1812, the Post reported that someone was to move into the above house: ‘Pakenham Boarding School – F. Batterbee returns her grateful acknowledgements to the inhabitants of Pakenham and its vicinity for the generous support she has experienced in her school upwards of 15 years. She begs to inform them that at the ensuing midsummer she will remove to a house at Walsham le Willows, lately occupied by Mrs. Catchpole, where she intends carrying on a boarding and day school for young ladies and hopes by unremitting attention to the health and improvements of her pupils to secure the approbation of such as may favour her with their patronage’’ The house in question was probably The Priory, before its Victorian extensions. It is also on record that the following year a Frances Batterbee, married to a cabinet-maker named Barnabas, privately baptised a daughter Charlotte. Walsham already had a boarding and day school for young ladies at the Rosary, Four Ashes (see article in Quarterly Review, Spring 2000). With the arrival of competition in the village a notice appeared in the Bury Post on 1st July 1812. ‘Mr Rogers respectfully informs his friends and the public that the general business of his school will be resumed on the 20th July – terms 20 guineas per year’.