The Game Place

Nicholas Bacon (1509-1579) was the upwardly mobile son of an overseer for Bury Abbey. As a lawyer, Nicholas acquired much property, including, in 1551, the Manor of Church House, Walsham. On Elizabeth’s accession in 1558 influential friends at court secured for him a knighthood and the Lord Chancellorship. With large houses in London and elsewhere, Sir Nicholas did not reside in Walsham, but his ‘Field Book’, written by his agents in 1577, is a detailed survey of the village (or town as it is called) whereby he could reckon up his assets. The book, containing 191 hand-written pages and bound in parchment, was kept with other Bacon documents at Redgrave Hall and was bought in 1992 by the University of Chicago where it remains. The Suffolk Records Society published a transcript in 1974.

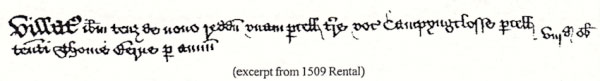

Of great interest to drama students is the brief mention of an open-air theatre on page 59: ‘Walsham Towne The sayd Game Place in the tenure of divers men to the use and behofe of the towne of Walsham aforesayd is customary ground holden of the sayd manor of Walsham and a place compassed rownd with a fayer banke cast up on a good height and havinge many great trees called populers growynge about the same banke, in the myddest a fayre round place of earth wyth a stone wall about the same to the height of the earthmade of purpose for the use of stage playes doth lie betwene the ortyard of the last sayd tenement on the north and the tenemente and ground in the tenure of John Vincent called Barnes on the south thone hedd thereof abutteth uppon the Hall Grene toward the east the other on the sayd ground called Barnes in parte and the customary close of Cycelye Margery in parte on the west parte and conteyneth – di.acre x perches.’

This is the complete Field book reference to the Game Place, transcribed with no modern punctuation. It is necessary to deal with some of the imprecise details, avoiding the extravagant claims made for this passage. Taking the statements in order, the ‘sayd game place’ refers to the mention of the tenement on the previous page where it is listed with adjacent properties. The Game Place is for the use of the whole village, and the ‘tenure of divers men’ presumably refers to a committee. The half acre ten perches (‘di.acre x perches’) of the last line is the overall plot within which is ‘a fayer banke cast up on a good height’.

This bank is presumably a wide-based earth rampart which could serve as a raised viewing platform for spectators of the ‘stage playes’. Even if they paid for admission, people were used to standing, and would not have expected seating to have been provided. The ‘good height’ is vague, but it could have been as much as 8 feet, in order to give a good sight line of the stage. In recent summers, plays have been staged at the privately owned ruins of Old Buckenham Castle in Norfolk. By reason of the circular earth ramparts the visibility and acoustics are acceptable, despite the weather. The ramparts have, over 8 centuries, aquired a small forest of trees, and they give some protection from the elements. At Walsham there is the implication that the ‘fayer banke’ was long established because of ‘many great trees’of substantial girth. The ‘populers’ were not today’s leggy Lombardy poplars, but rather the native black poplars. These, often painted by Suffolk’s John Constable, are quite rare now. They grow well in heavy clay soil and are closely related to the native willow. Walsham, first described as ‘in the Willows’ in 1534, was a suitable setting for both these trees which, with their dense screening, look very similar. Incidentally, the weeping willow of our modern village sign was not introduced till long after the 16th century.

In the middle of this shady banked area was the stage itself, round, of beaten earth retained by a stone wall. This would necessarily have been of flint. Imported freestone was too costly, and in any case there was an ancient tradition of circular flint and mortar walling, well demonstrated in the round-towered churches of East Anglia. The circularity is determined by the material, as flint cannot be cut satisfactorily to provide corners. Later domestic flint walls are squared off with brick, still quite an expensive material in 1577. The circularity was also the result of tradition, for round stages go back to classical times. Presumably the stage was raised to make actors visible to those standing at ground level, and a height of 3 or 4 feet would be sufficient. Access to this stage would be by wooden steps, and it is difficult, even dangerous, to make a dignified ascent wearing trailing robes or long skirts. To avoid this problem, actors would be on stage before the performance began, waiting their cue behind a screen. This screen would also conceal necessary costume changes, making a ‘tyring house’ (attiring house, dressing room).

Research by Kenneth Dodd in his paper ‘ Another Elizabethan Theater in the Round’ (Shakespeare Quarterly XXI – Spring 1970) suggests that the area surrounded by the bank and the trees was only 80 feet in diameter. With a total village population estimated at 800, a large space would be needed for spectators, so the stage itself was limited, perhaps less than 20 feet in diameter. With the thickness of the retaining flint wall and the screens of the ‘tyring house’, this only left 16 feet or so acting area. Walsham obviously did not stage the extravaganzas involving large casts and spectacular effects which medieval guilds, or mysteries, had mounted in major cities. With the Reformation, biblical pageants were in any case generally suppressed.

In the earlier years of Elizabeth’s reign small touring companies performed what are termed ‘interludes’. A generation later, in 1600, Shakespeare wrote a parody of such a production for the play-scene in ‘Hamlet’. Five visiting players are involved, and they carry all of their props and costumes with them. The action is stilted but effective. A less well-known but authentic interlude, printed in 1568, is ‘Like will to Like’ , or, as we should say: ‘it takes one to know one’. It concerns ‘what punishments followe those that will rather live licentiously then esteeme and followe good Councell’. The title states ‘Five may easily play this Enterlude’ and then lists the sixteen parts divided among five actors. Doubling was the norm even for Shakespeare’s London theatre, and the strategy was not without dramatic effect. Modern productions have used the same actor for the Ghost and Claudius in ‘Hamlet’, and the two Dukes in ‘As You Like It’. Lears’s Fool, addressed as ‘boy’, could well have played Cordelia, as all women’s parts were played by male actors on the Elizabethan stage. Even Shakespeare’s spoof of amateur dramatics, the ‘the tedious breefe Scene of young Piramus and his love Thisby; very tragic mirth’, required the heroine to be played by the bellows-mender in drag. We have no information about local amateurs, but there are references to professional touring companies such as the Erle of Leycesters Men performing in Suffolk. A member of this group, James Burbage, built the first theatre in London in 1576, and later his son Richard was Shakespeare’s principal actor.

In 1496 Thomas Berne gave 1 rood of land or pasture, parcel of the Conyger (ie: the coney-garth or rabbit warren) to the profit and advantage of the church of Walsham and the promotion and increase of the Guild of St. Mary and all other guilds in the town (Suffolk Record Office HA 504/1/17.18). Just before his death the following year he gave the town another piece of the Conyger containing 12 rood (SRO HA 504/1/17.19) making the half acre site quoted in the Field Book. Prior to the game place, the land was used as a camping close. A rental of 1509 held by the British Library (B.L.Add 14850 ff163-175) states that ‘The town there holds from new rent a parcel of land called Campyngclosse parcel of the tenement of Thomas Berne pa. 8½d’. ‘Camping’ was not a limp-wristed activity in Tudor times, for the word meant ‘a violent struggle’ and was applied to a rough-and-tumble form of football. The term ‘Game Place’, first appearing in a court roll of Walsham manor of 1533(SRO HA 504/1/19.8) also implies sporting activity, and perhaps was at first interchangeable with ‘Camping Close’. As village recreation areas, ‘Camping Closes’ are mentioned throughout Suffolk, but the county’s only other allusion to a Game Place is at Beccles. The site of the Game Place is a short distance across Summer Road, west of the Six Bells. Some have identified it with circular raised banks visible in modern times, but this is unlikely. Staunch Puritanism in the 17th century forbade Sunday sports and ‘Stage Playes’ and the site would probably have been levelled. There are references in Walsham Town Wardens accounts of the 1680’s (SRO FL 646/5/1) to ‘the gameplace’, (one word), but it is merely a placename, not an area in use. With 20th century building operations for two large houses in the vicinity, it is likely that all traces of the Elizabethan leisure centre are, as Prospero put it: ” melted into ayre, into thin ayre”.

Brian Turner 2004

Books consulted

- Dodd K. (ed) The Field Book of Walsham le Willows Suffolk Records Society 1974

- Dymond D.&Martin. (eds) An Historical Atlas of Suffolk Suffolk Institute 1999

- Happe P. (ed) Tudor Interludes Penguin English Library 1972

- West S.E. & McLaughlin A. Towards a Landscape History of Walsham Suffolk County Council 1998

FROM WALSHAM TO WATERLOO

If you go to the National Archives website nationalarchives.gov.uk and type in Walsham le Willows you will find the names of soldiers from Walsham who were discharged from the army. Thinking I might unearth some skleletons in the cupboard of some local families, I went to Kew to track them down. You’ll be pleased to know that the discharges were all honorable ones. Editor.

John Piott (or Pyat) was born in Walsham le Willows in 1781. Seven years later his father Bartholomew died aged 30. His mother Maria Pyatt (nee Polard) remarried in 1791 to William Gawswell who was probably the father of a child named William who was born the previous year.

In March 1800 John, aged 17, took the journey to Bury St. Edmunds where he enlisted in the 11th. Regiment of the Dragoons (Mounted Infantry). That same year his sister Susan died aged, the records say, “about 16”.

In 1808 British forces under Wellington (Then still Sir Arthur Wellesley) left for the Iberian Peninsula to combat Napoleon’s aggression in Spain and Portugal. The blue jacketed Dragoons were a light cavalry unit who covered great distances seeking out the enemy. In 1811 about the time of the battle of Albuera they were certainly in the thick of the action. It seems that in a skirmish John Piott received sabre cuts to his left hand and body and was captured by the French who imprisoned him in Portugal. The following year Napoleon withdrew many soldiers from the region to use in his ill-fated Russian campaign. John was probably released as Wellington pushed the French back. Whether he rejoined his unit or not is unknown but certainly in July 1812 the 11th. Dragoons were in the battle of Salamanca, one of the biggest operations of the war. After his defeat at Leipzig in 1813 Napoleon was exiled to Elba. However he was to regain power in France and in 1815 faced the British across the battlefield of Waterloo. John Piott was there to witness Napoleon’s final defeat.

After more than 17 years service in the Dragoons, John, who was a good and attentive soldier, was found to be worn out and unfit for duty. Now 36 years old and being described as five feet seven inches tall with grey hair, hazel eyes and a dark complexion, he was discharged in December 1818. He returned to Walsham and in 1820 married a widow Ann Haward (or Hayward). In census returns they can be found living in Palmer Street, John being described as a Chelsea Pensioner. Ann died in 1852 aged 77. John Piott was at this time 69 years old but records do not show what happened to him at the end of his eventful life.

In 1808 when Wellington’s forces were heading for the Iberian Peninsula a baby named Henry Hubbard was born in Walsham to Mary Hubbard who was unmarried. It is probable that she was the Mary Hubbard who married Abraham Payne in 1811. In later census returns they are shown living in Wattisfield Road. Mary had Henry baptised in 1813 in St. Mary’s Church when he was aged five. Mary died in 1865 aged 83.

In early 1831 Henry, now a farm labourer went to Bury St. Edmunds and enlisted in the 94th. Foot regiment for which he received a £5 bounty. He was 22 years old, five foot nine and three quarter inches tall with fair complexion, hazel eyes, and dark brown hair. In 1838 he was sent with his regiment to Ceylon but after a short time they were transferred to Madras in India where they were to remain for nearly 15 years. He was a man of exemplary character who received good conduct pay for the years 1838,1845,1846, and 1849. In 1852 he received a silver medal for meritorious conduct.

Henry was hospitalized in 1850 and 1851 with severe diarrhoea and again in 1851 with chronic hepatitis. It was noted in his records that his disabilities had not been aggravated by vice or misconduct. In 1853 at the age of 45 he was judged to be unfit for duty, being worn out from the length of his 22 years service and was discharged at Bangalore on November 30th. 1853. The whole regiment returned to England a few months later. There is no record of him in Walsham after this date.

Jonh Haward (or Hayward) the son of John and Hannah (nee Andrews) was born in 1807 and baptised on 3rd. March 1808 as John Andrews Haward. In December 1825 aged 19 he went to Cambridge to join the 43rd. Light Infantry. He was five feet seven and a half inches tall with a fresh complexion, grey eyes, and light hair. He had voluntarily enlisted himself for a bounty of £4 to serve King George IV and received a further 10s when attested. He was examined and passed fit to join the Infantry where he remained for 22 years. During his period of service the 43rd.’s served in Gibraltar and Canada but his records suggested that John Haward never went abroad, perhaps he was part of the H.Q. staff or trained new recruits. Hoever he rose through the ranks making sergeant by 1830. Two years later he was reduced back to private for fighting with a lance corporal. In 1835 he was a sergeant again, a colour sergeant in 1840 and by 1846 he had become a sergeant major.

He was discharged in 1847 aged 40. His records show that a modified rate of pension was to be decided upon by the Chelsea Hospital. He was descibed as being pock marked. It is not known what happened to him after his discharge. His parents John and Hannah are shown in the 1851 census living in PalmerStreet as paupers. Hannah died in 1869 aged 92.

James Turner 2004

FROM the PARISH REGISTER

The parish registers of Walsham (baptisms, marriages and burials) from 1539-1900 are transcribed and are now available on a CD Rom together with the Census Returns of 1841,1871 and 1891. You can get a copy from Ann Daniels of Bridge House – a bargain at £10.

There is just one gap in the registers, between 1641 – 1652. This was due to the political and religious upheavals at the time of the Civil War. Most of the registers give the barest of details but in 1652 Thomas Curee the new curate added extra information. In the burials register he gives details of three people who died and were not buried in the churchyard. Two of these were members of a Separatist sect who were denied burial in the churchyard. Instead they were buried in “a hole in Thomas Cooke’s orchard”. Thomas Cooke lived at Crownland Farm and his orchard was to the west of the house ie: the small field next to the public footpath. Full details can be found in an article by Jean and Ray Lock entitled “Early Congregationalism in Walsham-le-Willows” in Review Number 5.