19th Century Austerity in Walsham le Willows

Over the centuries there has generally been sympathy for the impoverished. The Poor Laws from 1601 onwards evolved into a system of helping those in ‘genuine need’ (as opposed to ‘wandering beggars and vagabonds’) and established the duty and systems by which each individual parish took responsibility for the care of the poor within its boundaries. The costs were paid for by the ‘Poor Rate’ tax levied in each parish on local householders, and appropriate arrangements were made to assist with the feeding and if necessary the housing of the destitute. ‘Settlement’ rules were established to discourage economic migration between parishes, where the best chance of getting Poor Relief lay in the parish of one’s birth. But there was always a tension in the balance between those in need and those who paid the costs.

Basic emergency relief to the sick or unemployed, and regular relief of a shilling a week to those past working age who had a roof over their heads were the commonest forms of assistance. There were however significant variations in the assistance provided – and also in its cost. By way of example the records of Thomas Nunn, ‘Overseer of the Poor’ of Walsham for October 1770, and signed off in approval by six of the principal rate-payers, show an average of seven regular recipients of such weekly payments at that time. These, together with the somewhat greater costs of running the local workhouse, typically came to a total of around £28 per month. There were roughly 180 householders in the village assessed for Poor Rate contributions. These ranged from £2 to £118 per annum, generally paid in instalments and sometimes in grain rather than cash. The higher figure was equivalent to £8000 today.

A parliamentary survey in 1777 of Poor Relief expenditure analysed the provision of workhouses. Significant areas of Suffolk, ravaged by the decline of the textile and agricultural industries, were arranging to meet their Poor Law obligations with a dozen large, but harsh, “Houses of Industry or Correction” that “incorporated” many of the parishes in their vicinity. On the outskirts of Stowmarket the ‘Onehouse’ institution was established in a building described as “palatial” according to an inspector of the time. It is still an impressive red-brick mansion built in 1781 in the classic Georgian style.

Perhaps 100 Suffolk parishes, including Walsham, were already providing smaller, local workhouses. A similar number of other Suffolk parishes had as yet no such provision of their own, including Stanton, Langham and Badwell Ash and these relied primarily on “Out Relief” to provide aid. Walsham’s modest “Guildhall” had places for up to 20 inmates, probably at times sleeping 4 or more to a bed. Inventories of the bed-linen and other furnishings were duly recorded in the parish records. The institution had been long established, convenient for compulsory worship at the nearby church. The primary work provided for Walsham inmates – it was a workhouse after all – was spinning. The able-bodied males of the village were expected to find work where they could, but that often entailed abandoning wives and children to the care of the parish – and contrary to the rule of law. Many of the inmates were unmarried women whose days of domestic service or freelance needlework were over.

The beginning of the 19th century was marked by mass unemployment following the end of the Napoleonic Wars. The picture of local poverty has been explored in ‘A Story of Walsham Folk’ by James Turner. Population growth, the introduction of new technology to replace agricultural labour, and a series of bad harvests, were starting to make the cost of the established system of Poor Relief unsustainable for individual parishes. With agricultural work unavailable, particularly in the winter, up to one third of the population of Walsham was dependent on charity to a greater or lesser degree. The following post was advertised at that time:

IPSWICH JOURNAL Saturday 28th April 1810

“Wanted Immediately: A Middle-aged man and his Wife, without any family, to superintend the poor in the workhouse of Walsham le Willows, in the county of Suffolk. Apply personally to the Churchwardens and Overseers of the said parish.”

Although the financial arrangements were not specified in the advertisement, we know that twenty years previously when Robert Buxton, worsted weaver, from Walsham was appointed to manage the Pakenham workhouse [At the Overseer’s Door: Whitehead] his net pay after expenses was roughly £50 per annum. He had however previously managed the Walsham workhouse at a somewhat lower rate. Nor was it an entirely risk-free occupation. On 9th March 1813 Mary Parker, pauper, of Walsham workhouse, was summonsed by the parish constable to answer charges before a Justice of the Peace that she did “abuse and ill-treat William Bainshaw, governor of the said workhouse”.

A survey taken in Walsham in 1832 [Walsham Village History Group Quarterly Review #23, October 2002: Turner/McLaughlin] showed the severe need locally for such organised help, modest and uneven though it may have been. But the overall tax burden continued to be criticised and savings had to be made. In 1834 the Poor Law Amendment Act founded ‘Poor Law Unions’ to consolidate and operate local workhouses to agreed standards throughout the country. Driven by the rate-payers this was an ambitious feat of Victorian organisation to provide consistent levels of assistance, but greater economic efficiency was the force behind it. The resultant hard living conditions were described by commentators such as Charles Dickens. Publication of Oliver Twist commenced in 1837, and some of the Walsham entries may remind us of Mr and Mrs Bumble. It was intended that entry to these institutions should be made as unattractive as possible, while ‘Outdoor Relief’ (which although more economical to provide was viewed as distorting the wages structure) would gradually be abolished.

Over time some 600 Unions were established nationally to replace the network of parish workhouses. Each Union was closely controlled by a Board of Guardians representing the parishes concerned who continued to pay for their parishioners by way of the on-going Poor Rate levy. In 1834 the function of the Walsham workhouse was subsumed into the Stow Union at ‘Onehouse’, previously the Stow ‘House of Correction’. Stowmarket itself at that time was a town with a population little more than twice the size of Walsham but it did have a purpose-built building in place. The Stow Union became responsible for some 31 parishes with a combined population in the 1831 census of 16,846. It could in theory accommodate some 500 inmates and staff. In the 1841 census it in fact housed 93 souls and for the remainder of the century numbers were seldom much more on a consistent basis. The enlarged catchment area was divided into administrative Districts into which the villages were grouped, including the Walsham le Willows District.

Initially the management resources of these enlarged Unions were modest although the Board of Guardians itself was large, as every parish had to be represented by at least one member. In addition to the Master or Governor there would be a Matron (usually his wife) and possibly a Supervisor of the domestic work carried out by the female inmates. In 1837 the services of a ‘Medical Gentleman’ were sought for the Walsham le Willows District of the Stow Union. At a time when free medical facilities were not available to the population at large the services of whoever was to be appointed (formal medical qualifications unspecified) were not restricted solely to the inhabitants of the workhouse.

SUFFOLK CHRONICLE AND WEEKLY GENERAL ADVERTISER AND COUNTY EXPRESS Saturday 20 May 1837

“STOW UNION. MEDICAL ATTENDANCE. THE Board of Guardians of this Union will on the 30th of May instant, proceed to elect a Medical Gentleman, for the Walsham Le Willows District of this Union consisting of the following Parishes viz.:- Ashfield Magna, Badwell Ash, Elmswell, Hunston, Hinderclay, Langham, Norton, Rickinghall Inferior, Stowlangtoft, Walsham le Willows, Wattisfield. The Salary for which, is to include attendance, medicine, midwifery, all surgical instruments requisite for the treatment of disease or accident, and every other matter used in medical relief, for all persons residing in any of the above Parishes, whether belonging to any Parish within the Union or not. Offers of Service and Testimonials must be transmitted under seal, before the 29th of May inst., to Mr. Robert Marriott, the Clerk, Stowmarket; of whom further particulars may be had, if by letter post-paid. Stowmarket, 11th May, 1837”.

The salary was also not specified in this case but similar posts were advertised elsewhere at £70 per annum “in addition to the Fees for Vaccination and Lunacy” – small-pox epidemics were a constant fear. The local appointee in 1837 may well have been Walton Kent who appears as ‘Surgeon’ living with his wife Frances and two children at The Beeches in the 1841 Walsham census.

In 1838 the joint posts of Governor and Matron were advertised. The duration of any such appointment varied considerably.

BURY AND NORWICH POST Wednesday 18th April 1838

“Governor and Matron wanted. Salary £100 per annum. WANTED for Stow Union Workhouse, on the 24th of June next, as Governor and Matron, a Man and his Wife, without encumbrance. Candidates will be required to produce satisfactory testimonials of their character, conduct, and ability, which are desired to be sent to the Clerk, free of any expense, on or before Monday, the 12th of May; after which time none will be received. The Election is intended to take place on Tuesday the 12th of June, when the Candidates will be required to attend personally. EDGAR, R. BUCHANAN. Clerk to the Stow Union. Stowmarket, April 17th, 1838.”

A further important post, that of Relieving Officer, covering the 11 villages of the Walsham District of the Union was also advertised:

SUFFOLK CHRONICLE AND WEEKLY GENERAL ADVERTISER AND COUNTY EXPRESS Saturday 16th June 1838

“Relieving Officer Wanted immediately. Salary £90 per annum…….A Steady active Man, between the age of 25 and 50 …Candidates will be required to produce satisfactory Testimonials of their character, conduct, and ability…”

With local knowledge the appointed officer was required to evaluate the cases of all persons applying for medical or poor relief and to authorise emergency relief or entry to the workhouse. It was a responsible role and the salary on offer reflected the discretionary power held. The proposed salary would have been three times that paid to the average wage-earner in 1838, equivalent to £7500 today.

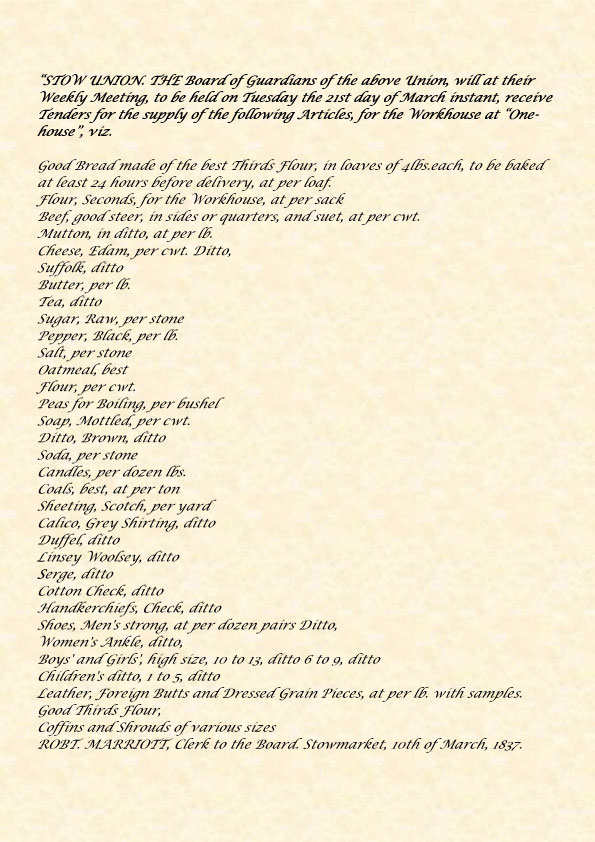

Thrifty management discipline was applied to the workhouse budget by those appointed to its guardianship. Supplies were sourced as transparently as possible by way of a periodic tendering process. The names of those awarded contracts would then be published openly. The process also provides graphic insight into the living conditions of the inmates.

BURY AND NORWICH POST Wednesday 15th March 1837

Whatever the quality of the supplies, it is likely that the reputation of these places for poor and limited food was justified. Bread was the mainstay of most meals, possibly combined with soup or cheese. Peas (dried – boiled for Pease Porrage) were the only vegetable bought in. The “Second” grade flour was used in the workhouse itself to feed the residents (flour, salt and water made “pudding”) while the coarser “Third” grade flour was distributed to families on Outdoor Relief via the weekly “dole”. The bulk purchase of coffins and shrouds was also a sad inevitability of these institutions. Stow Union had its own Burial Ground next to the detached Infirmary. What was less spoken of was the fate of paupers without family or friends to pay for their funeral. In 1832 the Anatomy Act was passed by Parliament, seeking to eliminate grave robbing – the illegal supply of cadavers to the medical schools for training purposes. As a result the workhouses and asylums became the primary source of supply with an unofficial but not illegal trade in the supply of the corpses of paupers to the dissecting tables of the local medical schools. This was also a source of undeclared income for workhouse employees.

Often the workhouse residents were suffering from mental health problems. By the time of the 1871 census they would be more widely identified with confident precision as either “Imbecile or Idiot” or “Lunatic”.

CHELMSFORD CHRONICLE Friday 24th August 1849.

“Dunmow police report.—On Sunday evening last, police constable Humphreys, when on duty near the Victoria public-house, Dunmow, discovered a man sprawling in a ditch of water, trying to get up the bank, and from his strange manner was induced to take him to the station. The man was respectably dressed in black, and gave his name as H—- B—-, of Walsham le Willows, Suffolk: he is evidently lunatic, but perfectly harmless and quiet, and is supposed to be a person who travels about at fairs with a dancing booth. Having been taken before the Rev. H. L. Majendie on Monday, he was by that magistrate sent to the Dunmow Union workhouse, where probably his friends will claim him.”

Living conditions at Stow Union were both harsh and demoralising. Unemployed male inmates capable of physical labour were employed in breaking up blocks of granite stone. The resulting broken stone, small enough to go through a specified sieve, was then sold to the local quarries for road mending at the original cost price of the granite – 11 shillings per ton (or say £60 today). The Guardians were reluctant to see the inmates, housed and fed without charge, benefit from further income that might impact on the wages of those gainfully employed outside.

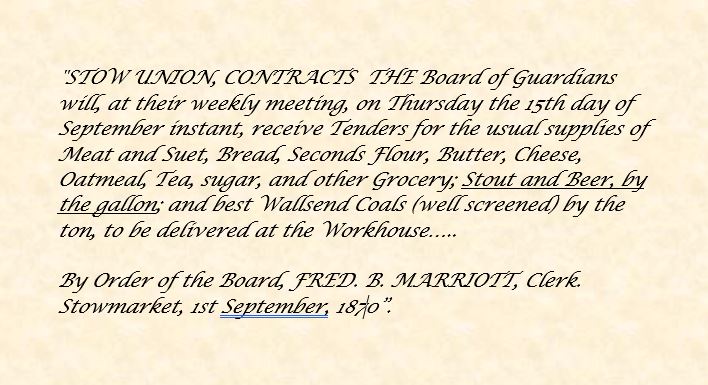

However from the 1870’s onwards there are indications that some aspects of workhouse life had started to improve.

THE IPSWICH JOURNAL Saturday 10th September 1870

THE IPSWICH JOURNAL Saturday 11th June 1870

“STOW UNION. SCHOOLMISTRESS WANTED. THE Guardians of the Poor of this Union will, at Their Meeting to be held on Thursday, the 16th day June next, proceed to the election of a Schoolmistress for the Girls in their Workhouse (subject to the approval of the Poor Law Board). The Person appointed must be a single woman or widow without encumbrance, and fully competent to perform all the duties required of her by the regulations of the Poor Law Board and the Guardians. Salary £20 per annum, with board, lodging, and washing, and such further sum as the Committee of Council on Education may award. Applications in the Candidate’s own handwriting, stating age and present occupation, with original testimonials of recent date as to character and ability, and certificate, must be sent to me at my office in Stowmarket, on or before Wednesday, the 8th day of June next; and such candidates who may be selected will have notice to attend on the day of the election. By order of the Board. FREDK. B. MARRIOTT, Clerk to the Guardians. Stowmarket, May.26th, 1870”.

THE IPSWICH JOURNAL Saturday 4th April 1874

“STOW UNION. CONTRACTS. THE Board of Guardians will, at their weekly meeting, on Thursday, the 16th day of April instant, receive Tenders for the following articles and things for the remainder of the year ending the 25th day of March, 1875; namely for- Port Wine by the bottle and half-bottle, exclusive of the bottles, and for Brandy and Gin, by the imperial pint and half-pint, to be furnished in the Walsham-le-Willows district, on application by the paupers having orders, for which purpose such Contractor is to appoint his own stations and pay his own agents in such districts, such stations to be at Walsham-le-Willows and Norton; at which stations the Wine and Spirits shall, at the Contractor’s expense, be served out to the paupers in such quantities, and at such times as may be required, upon a ticket from the Relieving Officer. Tenders with samples must be sent to the Workhouse, addressed to the Chairman of the Board of Guardians, on the morning of the 16th day of April instant; any sent before that time will not be opened, and none will be received after Half past Ten o’ clock. N.B. The samples of Wine and Spirits to be delivered in common pint black glass wine bottles. All Tenders must be made in the prescribed form ……”

In the years up to 1880, as the number of residents remained well below capacity, serious consideration was given to closing the Stow Union Workhouse on grounds of economy and efficiency with the inmates to be transferred to adjoining Unions and the building to be converted for use as a lunatic asylum. It was argued that while the numbers of paupers applying were thankfully in decline there had grown at the same time an on-going increase in the numbers of mentally ill applying. While some of the adjoining Unions were prepared and able to provide facilities for the parishioners from the Stow Union members, others were not and the plans progressed no further. These discussions coincided with a change in management. Two years earlier the Master of the workhouse had an unfortunate accident.

EAST ANGLIAN DAILY TIMES Monday 28th October 1878

“STOWMARKET ACCIDENT.—A few evenings since as Mr. Wiggins, master of Stow Union Workhouse, was standing on the platform of the railway station, awaiting the arrival of the train, he turned round suddenly and missed his step falling across the line on the rails breaking two of ribs and severely spraining his wrist. Mr. Harry Dove was soon in attendance, and rendered the necessary assistance, and, under whose skill Mr. Wiggins is rapidly progressing.”

But sadly in 1880 Mr Wiggins, aged 53, died from heart failure following 20 years’ service at Stow. He was succeeded by Neville Mark Simmonds aged 27. Shortly afterwards Simmonds was initiated into the local ‘Phoenix’ Freemasons Lodge. He was ambitious to progress in his career. By 1891 he would be master of the Holborn Workhouse in London and by 1901 Master of the Marylebone Workhouse – with 28 staff and up to 2,000 permanent residents.

In the 1881 census there were 138 residents in the Stow union. There were eight originating from Walsham including a lone child of six, an aged male “imbecile”, and a 42 year-old mother duly noted as “unmarried” with her four children. Perhaps some of these benefitted from the following.

EAST ANGLIAN DAILY TIMES Saturday 30th July 1881

“STOWMARKET. Treat to Workhouse children. The children belonging to Stow Union Workhouse were, on Thursday. invited to Mrs. Fison’s, where they had a bountiful tea on the lawn in front of the house, followed by games and prizes, During the evening Mrs Fison took them round the gardens, when they were allowed to help themselves to an abundance of ripe fruit.”

But by the start of the new century charity may have been wearing thin. It was commented that some workhouse inhabitants were living better than the ‘common man’. “WHO WOULD NOT LIVE IN THE WORKHOUSE?” thundered, tongue perhaps not entirely in cheek, the

PALL MALL GAZETTE Wednesday 5th June 1901

“The Stow (Suffolk) Union, in the last tender for six months’ supply of groceries, stipulated that Cadbury’s cocoa must be supplied, a high-class quality proprietary article costing nearly one shilling per pound more than the finest quality ordinary cocoa and nearly two shillings per pound more than the article usually found on the working man’s table. Then, Colman’s mustard is imperatively demanded, and it must be “Double Superfine”—that is, the highest priced on the market. The many thousands of persons in all conditions of life who swear by Scotch oatmeal will be interested to learn that it is too common for the Stow Union, which must have the swagger ” Provost Oats,” costing 5s. per cwt. more than the ordinary person outside of the workhouse thinks ample for the best meal. After these instances it is not to be supposed that ordinary rice is good enough for Stow Union epicures. Nothing cheaper than Patna or Japan rice tempts their dainty appetites, nor will English or Irish butter or margarine. Best salt and best fresh Danish butter must be supplied, whilst the sugar demanded is of a quality foreign to the table of the working-man, costing 4s. per cwt. more than he can afford.”

Whatever the merits of the charity provided, the workhouse had nevertheless become a destination of fear and despair. Migration from the countryside to the cities may have transferred the scale of social problems but commentators have noted the shame and degradation of all of those who were reduced to such a state of destitution, and the abuse, cruelty, disease and squalor they subsequently suffered. These were the judgements of the time and not just by the standards of today. When I was writing this I found that there are people still living locally for whom the word Onehouse (or rather “One-‘us”) forms all too graphic a reminder of the deprivation and fear of times not long gone. The role of the workhouses would subsequently fall away with the establishment of the Welfare State and the National Health Service in 1948. Onehouse became a hospital and was subsequently converted for residential use – it is now owned by a Housing Association.