Graffiti at St Mary’s

A church, it might be thought, is an unlikely place for unauthorized inscriptions, yet St Mary’s, Walsham le Willows, in common with many other sacred buildings, has a host of scribbled messages. They are mostly scratched into the soft stone, called “clunch”, which forms the architectural framework. This stone, usually brought at great expense from Cambridgeshire, was used sparingly. The main structure of East Anglian churches is flint, and the interior walls were plastered and painted. These wall surfaces no doubt harboured many graffiti, but they were periodically limewashed, and in the 19th century they were often covered with sharp-sand and cement. In St Mary’s this is fairly impervious and difficult to indent, so most surviving inscriptions are on the clunch framework. Nearly all of the graffiti can be seen in the nave, the main body of the building. The staircase to the ringing chamber also bears numerous inscriptions, mostly by bell-ringers. As this staircase is not open to the general public, these graffiti will not be dealt with in this article.

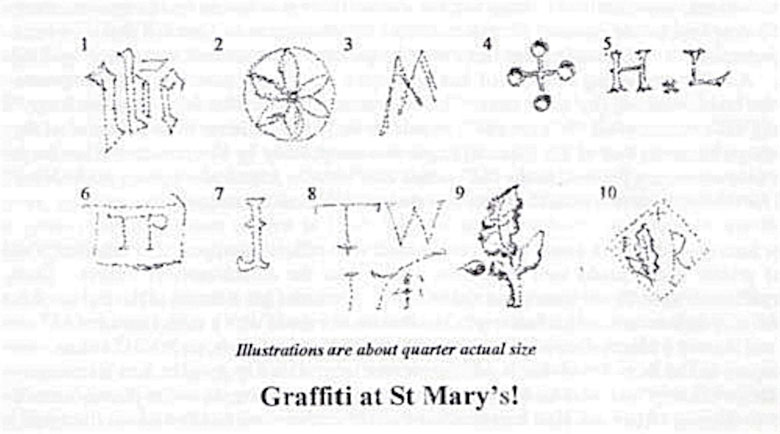

Back in the nave, a certain type of inscription occurs at least three times (others may yet be discovered) and it reads as “ih’c” in Gothic lettering. It is commonplace in a Christian context, and it stands for “Jesus”. Some think theses are Greek letters, but most modern scholars take it to be a later medieval device formula. This device can be seen faintly on the second pier or pillar back from the pulpit, on the south aisle (1), then, more clearly but inaccurately, on the fifth pier back, and thirdly, in larger letters, on the tower arch, south side, directly adjacent to the door of the ringers’ staircase.

Graffiti are usually subvervice, but “ih’c” was a hallowed symbol, particularly in the late 15th century. On the outside of the building it is given pride of place on the flushwork of the clerestory. It can be seen at the east end, “bound” by a larger “S”, presumably for “Sanctus”, giving the device a passing resemblance to a portcullis. This developed form was common in flushwork by the important mason Thomas Aldryche who worked here around 1480. The three graffiti are probably earlier. The letters, presumably copied from a church artefact, were scratched on the stonework in the hope of divine grace and assistance. Near the first “ih’c” there are some faint scratches in a late medieval hand which might read “Dominus vobiscum” – the Lord be with you.

Another type of graffiti, also a private gesture invoking supernatural aid, is termed “aprotropaic”. There are several of these which involve the use of a pair of compasses, so they are not casual scratchings. The most eye-catching of these, looking surprisingly fresh, is on the pier near the first “ih’c”. It is on the northern side, facing the centre of the nave (2). This geometrical daisy, like many other circles found throughout the church, was inscribed to keep witches away. There is even one on the external stonework of the priest’s doorway, on the north of the chancel. The parishioners must have felt that their vicar was in need of protection. It is difficult to date these circular graffiti, for witchcraft was feared well into the 17th century. A rather interesting example of late apotropaic marks, not inscribed with compasses, is a group near the main entrance, the north door. On the second pier from the west are some letter “M”s crudely drawn, like two inverted “V” s, or “W”s upside down (3). The letter form is typical of the 17th century. Perhaps when the cult of the Blessed Virgin was swept away by Protestantism there lingered a belief in her intercessionary powers, so the “M” stands for “Mary”. Alternatively, the upside down “W” might stand for “Down with Witchcraft”. There is a strange “W” near the ringers’ doorway.

Graffiti were usually scratched in secret and likely to meet with, official disapproval. Protestant Walsham however has graffiti which could well have been made under the churchwardens’ orders. These are crosses of a particular style, found throughout the building. The cross has a button at the end of each arm, so it is heraldically known as a “cross botonny”. The buttons are made with a drill, typical of 17th century stonework, and there are twenty-four crosses, three on each of the eight sides, on the 14th century font (4). After the damage to the faces below the bowl, the crosses were added to give the font a more religious aspect. “Crosses botonny” can also be found on the east of the chancel arch, in the priestly area, five at least on the north side. They are also scratched on the 15th century oak bench ends in the north aisle. These benches were once free standing, and we cannot be sure of their original position.

Apart from these religious inscriptions, most of our graffiti reflect that tiresome human urge of attracting personal attention, and there are many scratches, vandalistic scorings of the “Kilroy was here” type. We can assume they were a form machismo, and that the carvers were male. The carvings are generally without artistic merit, but on the pier already mentioned, the second back from the pulpit, there is a well-cut “H*L”, in lettering characteristic of the 17th century (5). The only HL in the parish records from this time was Henry Lincoln who died in 1626. The initials, “TP” are on the respond (the half-pier) near the chancel arch, north side (6). Again it appears to be a 17th cenury hand, but in this case there are many in the parish records who could have inscribed it. All of them Thomases, we have Padnall, Page (three generations), Palfrey, Parker (three generations), Peage. Polard and Prime. We may assume that Thomas P was quite tall, for the inscription is nearly six foot up. In the same area are several “R”s, “W”s and other initials in the 17th century style, but it is daunting to track down all the Richards and Wiiliams in the records. Even more difficult to trace is the 17th century “I” defiantly scored into the priestly space knoen as the “sedilia” on the south side of the chancel (7). “I” was generally the initial of “John”, and without the surname the initial quest has to be inconclusive.

Apart from the style of the lettering there are few clues to the dates of the inscriptions. One sure test however is; if the scratches are covered by the present benches then they were made before 1878 when the seating was installed. On the pierwith the “W”s, almost obscured by the bench, are the initials “TW” (8) perhaps scratched with a guiding rule, and an uncompleted attempt at the date 174. This narrows the search, and the miscreant may have been Thomas Wicks or Thomas Worker. This pier nearest the door was obviously a haven for “bad boys”. They have scratched initials, aimless doodles, even the Union Flag with misplaced patriotism. Similar activity is to be found on the north aisle window-sill to the right of the organ. Until it was moved in the 1990s to unblock the window, the mighty instrument concealed this area. It was installed in 1870 and like most organs of that period, was originally hand-blown. Generations of lads worked the pump hidden from view. During the sermon they could make their bid for immortality, and several full names, scratched and penciled, can be found there. They are mostly dated from the 1930s and 40s, and the names are still borne in the village.

It is difficult to find 15th century masons’ marks. These were usually simple geometric designs, and in certain lights there are certain scratches high on the arches which could be interpreted as such. They were cut in the masons’ yard and served simply to identify the workman when the stone was assembled. If the stone did not fit then he could be referred to for adjustments to be made. The marks were not meant for cosmetic display and most seem to have been scraped away by the builders.

This brings us to a piece of work sometimes said to be a mason’s mark, quite wrongly. Tucked behind the pulpit, it is not a graffiti at all, but a relief carving overlapping on to the adjacent stone (9). It shows an oak-leaf and two acorns, one of which has come out of its cup. The present stone pulpit was installed in 1878, but it was preceeded by larger wooden structures which could have offered some concealment for the carver, scraping away for hours. He may have been merely illustrating the saying “tall oaks from little acorns grow”, part of a poem written in 1776, but this sounds unlikely and does not account for the concealed position.

Perhaps the acorns reflect something subversive. The Stuart cause was associated with the “Royall Oake” from the earliest days of the Civil Wars, and later the young Charles II, after his defeat at the Battle of Worcester in 1651, hid from the Cromwellians in the oak tree at Boscobel. He escaped. like the acorn detached from its cup. This may be a romantic theory, but it certainly fits in with Walsham during the Civil Wars. Most Suffolk villages were Parliamentarian, and Walsham had its own Roundhead Captain, Ralph Margery, praised by Cromwell and buried in the churchyard in 1653. Support for the Stuarts would have been unwise during these times, and a latent royalist would have had good reason to make this loyal gesture secretly. A similar device, with a letter “R2”, but without the detached acorn, is scratched on a squared stone on the front of the porch (10).

Brian Turner

What the Papers Said

Bury Post 14th October 1873

An inquest was held in Walsham le Willows on the body of Walter Steward aged twenty-seven. Witness Wlliam Pollard, who was in the employment of Robert Nunn said,

‘We were engaged in cutting chaff when the deceased threw his hat down, smacked his hands and said, “I.ll have a round with you, old fellow.’

Witness Charles Thorpe, steward to Mr Easlea in whose barn the machine was at work, said they were larking and laughing just nannicking about when they fell into the deep straw.

‘I should never have expected that anyone could be hurt from such a short fall. However the deceased did not move and when we pulled him up he said, “I think I’ve broken my back-get the doctor.’

Doctor Short found him to have a fractured spine that caused paralysis. He died seven days later. Verdict: Death from accidental injuries.