Farming in Walsham in the Middle Ages

The account rolls of which twenty-six, mostly from the 15th century, survive are the annual balance sheets of the manor and give different information. Officials ran the manor for the absentee lord and were obliged to account for every tiny item. Each account is set out in a particular pattern, with income followed by expenditure. On the reverse of the parchments, usually about one metre long, are the stock accounts ie: the grain and animals remaining on the manor farm.

The names of tenants who held land and houses by paying fixed (permanent) rent are listed with details of the property, its size and location. In addition to cash rent, villeins (as opposed to free tenants) owed works and services on the lord’s own (demesne) land in return for their houses and land. These works included ploughing, carrying and spreading manure, weeding or hoeing, mowing of hay, reaping at harvest time and running errands. The works were a tremendous burden, taking tenants away from their own fields at times when they most needed attention. By the 15th century it was becoming difficult for the lord to find enough labour to work his demesne land: after the Black Death of 1349 the population in Walsham halved and the peasants were in a better bargaining position. They gradually began to pay ‘compensation’ to the lord instead of doing the services and he was obliged to pay men to work on his land. This become uneconomical and so the demesne land was gradually leased to villeins for a set number of years for cash rent. This is also listed giving the name of the tenant and the size and location of the land. Rents were always the largest and most profitable items. Among the names of the lord’s own fields were Dovehouse Wong, Doucedeux and Master John’s Close. The open fields, where both the lord and his tenants held narrow strips of arable land, were Mill Field, North Field, South Field, Well Field and West Mill Field.

As well as a set number of works and services tenants were required to carry out boon works at short notice. These consisted of Ploughale – winter ploughing with food and ale provided, Reapale – getting the harvest in and Tumbrel – tenants providing either a cart or man-power for the lord’s carts. There are two good examples of the latter in the early 15th century. In 1402/3 (the accounts ran from Michaelmas to Michaelmas) twelve men with six carts went to Haddiscoe in Norfolk to fetch timber for a new windmill. Haddiscoe is on the marshes with no obvious woodland so presumably the timber had been imported into Kings Lynn and shipped down the Waveney. In 1406/7 three carts went to Santon (probably a mis-spelling of Stanton) to fetch bricks and take them to Westhorpe, presumably to the hall there. Walsham shared a lord/lady with Westhorpe and lady Elizabeth Elmham may have been carrying out alterations or extensions after the death of her husband Sir William early in 1403. Twelve pigeons, forty lambs and thirty-five capons were among the items bought by Walsham for his funeral feast. He had spent Christmas at Westhorpe Hall supplied with a boar and game birds from Walsham. Expenses were also allowed for six men looking after the manor for four weeks after his death.

Most houses had surrounding land, up to 40 acres in the case of some on the outskirts of the village. Those who lived in the street with only a garden or small plot, had additional land in the open fields. At least 10 acres were required to sustain an average family. Most tenants also had a strip of meadow in the Mickle or Great Meadow at West Street to provide hay for winter feed.

But both Walsham and High Hall had their own farms run with labour supplied by the works and services of the villeins.

Only two accounts survive for High hall, the others are for Walsham manor after they were amalgamated. The demesne land of High Hall is listed in a Rental of 1327 and comprised a total of 198 acres, all at East End near the hall. Amongst the fields mentioned by name are St. Katherine’s Croft, Ulversrowe and Thirty Acres. All these fields were ploughed, harrowed, sown, weeded and harvested by villein labour. Buildings in the farmyard included a granary, threshing barn, stable, ox-shed, poultry-house, sheephouse and bakehouse. Sheepcote Croft also belonged to High Hall. The sheepcote was an elaborate structure designed to give some protection from the elements during lambing, shearing etc.

Walsham manor farmed c.236 acres as demesne including Brooms Wong, Old Toft and Childerwell. Apart from strips in the Mickle Meadow, 17 acres called Little Meadow was the lord’s own meadow. All this land was quite close to the manor hall and farm in Summer Road. Each manor had a dovecote supplying pigeons and each manor farmed fish. There were many days in the medieval year when, for religious reasons, meat was not eaten. Instead fresh water fish were bred in fishponds. Walsham manor had its own, still known as Fishponds and High Hall would have kept the moat well stocked.

There were four woods belonging to the manor; Ladys Wood was on the south parish boundary with Badwell Ash, North Hall Wood was north of Walsham manor in Summer Road, High Hall or Nether Hall wood was north of High Hall manor at the east end of the parish and Luchesdell Grove was close to where Bribery Cottage now stands. Tenants could buy the underwood or coppicing of small areas of these woods for building, fencing, thatching etc. and also standard trees with oak, ash, elm, white and black poplar being the most common. Ditches surrounded the woods with hedges made of faggots ie: dead hedges, to keep animals out. Tenants were paid 6d to make 100 faggots, about 1½ or 2 days wages.

Costs of the ploughs and carts include 8d a day to William Saddler and his son from Stanton making leather collars, saddle-pads etc. Trees were felled and the timber shaped to make and mend ploughs and carts. Metal plates for carts were made from old iron. Buildings were thatched, barns repaired and gates made. Great emphasis was placed on gates, doors, locks and keys; security was obviously essential. There were hungry peasants about.

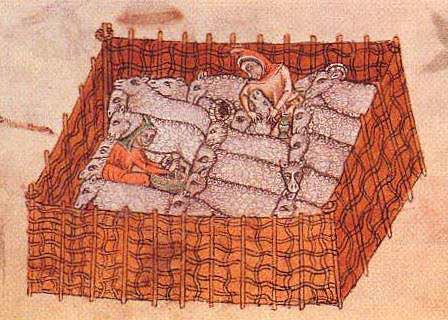

Tar and salve were bought for dealing with sheep disease and red ochre for marking after shearing. Hurdles were made for enclosing the sheep. Unless they paid an exemption fine, everyone’s sheep were folded with the lord’s flock at night so that he got the benefit of the manure. Robert Margery was the hurdle-maker for many years. In 1402/3 it cost 2s 6½d to wash and shear 202 sheep. Sheep were milked for cheese making (see illustration).

The permanent ploughmen were paid 8s a year plus food. One of them, William Man, was given an extra 2s for good service. This may have been a retirement gift because he is recorded as being ill and his son John then became the plough leader.

Walsham appears to have been a fairly benevolent manor and the harvest costs reflect this. They include wheat bread (not normal peasant diet), ale, mutton and other meat, pigeons, herrings and other fish, milk, cheese, eggs, butter, oatmeal (for pottage), salt, pepper and even saffron in one account. Candles were always included, presumably to light the hall or barn for the late meal, as every hour of daylight would have been spent working in the fields. Gloves were also bought to protect the hands of some workers. When tenants carried out boon works they each received a loaf of wheat made from a 20th of a bushel for their mid-day meal. But for their supper the free men had wheat bread and the villeins had a loaf of mixed corn – maintaining the status quo!

Two bushels of wheat, rye and peas were sown per acre, 3 bushels of barley and 2½ – 3 bushels of oats. Unfortunately yields are not given per acre so no comparison can be made with today’s harvests, although their yields would certainly have been much, much less. Although they lacked the fertilisers and herbicides that modern farmers use, medieval men knew that seed and stock needed renewing from time to time. The bailiff journeyed with carts to Bowthorpe near Norwich to buy fresh barley seed and animals were also bought in. After supplying the manorial servants, baking bread for harvest and for the lord and his guests at Westhorpe and feeding the animals, the surplus wheat, barley, oats and peas were sold, sometimes to local people, sometimes at Bury. The price varied considerably from year to year but it is noticeable that if it was kept back and not sold until the following year ie: when stocks were running out, it fetched a higher price. This extract is from an account of High Hall manor dated 1327.

- Sales of corn – 21s 8d received from 5 qrs. of wheat sold around Christmas, per qr. 4s 4d.

- 23s 4d received from 5 qrs. of wheat sold in Lent, per qr. 4s 8d.

- 30s received from 5 qrs. of wheat sold at Easter, per qr. 6s.

Straw including pea straw was sold to local men. There is evidence that some form of ridge and furrow ploughing was used. The seed was sown on the ridge with drainage furrows either side to drain off surplus water. There are costs for corn being weeded, teasels mown on fallow land before ploughing and bracken cleared from barley.

The stock accounts list all the types of grain remaining in the grange, newly harvested corn and details of sales. These include wheat, rye, barley, oats, peas, beans and bullimong (a mixture of oats, beans etc. sown together for animal feed). Animals included carthorses, stots (either horses or oxen used for ploughing), colts, oxen, bulls and bullocks, cows, steers and heifers, calves and the hides, dressed or tanned of all these animals. Sheep included rams, wethers, ewes, hoggets and gimmers and lambs. In 1390/91 a total of 946 lambs were in the custody of several named shepherds. Animals were delivered to Westhorpe for the lord’s larder and also fed to the officers who attended the manor court. Fleeces, sheepskins, pelts and lambskins had to be weighed or counted – one lamb was not sheared because it was too weak. Capons, hens, cockerels and eggs were part of rent paid by tenants. In one year the dovecotes at Walsham and High Hall manors produced 543 pigeons which all ended up on the plates of the lord and his guests at Westhorpe. Some accommodation was available at Walsham manor and was used by court officials when the court lasted for two or three days. Pepper and cumin were paid as rent and always entered – ½ lb of each.

Ploughing services and all the other works were entered in the stock account. Winter works included ploughing, carrying manure, gathering stubble, weeding, harrowing rye and oats, sowing furrows of wheat and peas, making drainage furrows, stacking straw for the thatcher, filling carts with dung and spreading it upon the land, making hedges round the woods, stopping up gaps in the hedges and shredding withies for making hurdles. Each year, along with the ale-tasters, were elected a reeve, a hayward and a woodward. These were local villeins who took it in turns to carry out supervision of the works and services and to collect rents. By the 15th century they were able to avoid these onerous tasks that would have interrupted work on their own land and made them less than popular with their fellow men, by paying a fine. Instead the work seems to have been done by a bailiff who was an official employed and paid by the lord.

Although only twenty-six of these accounts survive, used together with the information from the court rolls and rentals, it really is possible to build up a picture of Walsham in the middle ages. I hope this goes some way towards explaining my obsession with the people and the places involved and help my friends to understand why I bore them to death with it!

Audrey McLaughlin

Note: I have printed a full translation of two accounts ie: 1402/3 and 1406/7 together with an explanatory introduction. If you would like to learn more about medieval farming in Walsham, you can buy a copy from Rob Barber or Brian Turner or at one of the meetings of the Walsham Village History Group.

What the Papers Said

Bury Free Press 20th January 1877

A poor woman in Walsham le Willows was heating her oven after cleaning it out when she was seized by an epileptic fit and fell on the burning embers that had just been drawn from the oven. A woman named Moore found her after a short time with her clothes on fire and a man named Cason, who was passing at the time, extinguished the flames. Dr Short quickly attended the woman who was dreadfully burnt on her right side from wrist to shoulders and on her breast.

Great doubts are entertained as to her recovery.’

Bury Free Press 31st March 1877

‘The late accident by burning. The poor woman, the wife of James Adams, who met with a fearful accident in the village reported about ten weeks ago, expired after the most intense agony on Sunday last.

Every attention and care had been taken with the poor creature but without avail. The deceased had been subject to fits without warning for the past few years.

She leaves a husband and six children.’

Bury Free Press 26th May 1877

‘Death by Drowning – We much regret to state that Mr. John Thurston, farmer of High Hall in the parish of Walsham le Willows, was found drowned in a pool near his house on Friday last. At an inquest it was found that the intellect of the deceased was impaired and his body in a very weak condition.

Eliza, the wife of William Blake, who worked for the deceased for some years said that Mr Thurston said he was going out to give corn to the horses but when she looked for him found him in the moat in front of the house immersed in water.

Robert Hunt and Robert Frost of Finningham got him out and when they turned him over he appeared quite dead.

Dr Short of Walsham said he had known the deceased for nearly ten years. When he attended the incident he found no marks of violence. It was his belief that the death was accidental.’

100 Years Ago in Walsham le Willows – Spring 1902

Bury Free Press 26th January 1902

At Ixworth Petty Sessions Gordon Locke, a farmer of Walsham le Willows, was charged with killing a pheasant without having a licence. He was fined £1.’

Bury Free Press 1st March 1902

Miss Caroline Martineau, a familiar figure to Walsham, passed away at her London home. She was the youngest sister of Mr John Martineau. The deceased lady had been in failing health for some time having been confined to her room for a few weeks. Her death was not unexpected. She was cremated at Woking. Many will lose a true friend of cheery and optimistic disposition who took great interest in the people of the village and much good was done by her in an unassuming manner.’