Captain Raphe Margery – Walsham’s Ironside

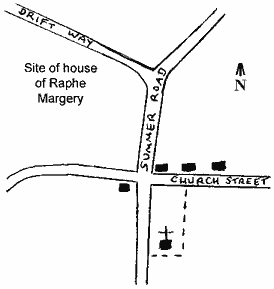

Raphe Margery, one of Cromwell’s captains, was a member of the Margery family who had lived in Walsham for generations. Raphe’s grandfather, John, lived in a seven-roomed house, long since demolished, on Summer Road in the vicinity of the present Willow Court. On the death of John in 1588 two of his sons left Walsham to make their fortune elsewhere. One of these sons was Raphe’s father, Richard, and on his marriage, he made his home in Swardeston, Norfolk retaining lands in Walsham. Raphe was their first child and was born in 1592. At some time during the early part of the 17th century Raphe came to live in Walsham, probably to look after his father’s interests there, and to take over lands inherited by his brother Samuel, who was a priest, paying him a yearly rent.

In 1619 he was married at Hunston church to Abigail Hall, whose father, William Hall, had been evicted from his living at Redgrave by Bishop Jegon for refusing to conform. He was one of a group of clergymen in the neighbourhood who shared a burning desire for further reformation of the church. They were all intelligent, well-educated men, one of them, Clement Raye of Wattisfield, being famous for his preaching and conversion. He was a friend of the Margery family, as were many of the other clergy. Abigail was seven years old when her father lost his living at Redgrave and she and her brother were left motherless at an early age. In his reduced circumstances their father took in students, preparing them for Cambridge University, and it is not surprising that Abigail, as she grew up, developed strong views about the religious issues surrounding the evictions of her father and his friends, and at the same time, a strong sense of grievance. In choosing Hunston church for their wedding, Abigail and Raphe demonstrated their convictions and feelings; the incumbent there was Richard Chamberlain, another friend of William Hall, who had been reprimanded by the Bishop of Norwich, but not evicted.

Raphe and Abigail began their married life in the house in Summer Road, and between 1620 and 1637 they had eight children. In 1635 when Raphe was serving as church warden, he refused to conform to the new rules for church wardens issued by the new Bishop of Norwich, Matthew Wren, who was determined to stamp out non-conformity in his diocese. Raphe was excommunicated from Walsham church. In 1638 Abigail was also excommunicated from the same church, for reasons unknown. The incumbent of Walsham could not bring himself to exclude her, but the forceful rector of Finningham rode over ‘and caused her to be carried out of the church…..and she coming again into the church ….. he caused her again to be put out…..’ [modernised spelling] Some months after this painful scene, in January Abigail died. She must have made her peace with the church authorities, for she was buried in Walsham churchyard. Her father William Hall, who had been living with the Margerys since their marriage, also died in the summer of 1639. He had become well known as a preacher and was remembered as such in several Walsham wills.

Raphe emerges from obscurity again in 1641. Sir Symonds D’Ewes of Stowlangtoft raised the subject of the persecution of the Margery family in Parliament during a debate on the Suffolk Ministers Petition. By 1643 when Parliament was at war with the King, Raphe offered to raise a troop of horsemen to fight for Parliament. Cromwell, seven years Raphe’s junior, and at that time a Colonel mustering forces in Cambridge, wrote to the gentlemen of the Suffolk Committee of the Eastern Association. The letter [modernised spelling]reads: ‘I beseech you, give countenance to Mr. Margery. Help him in raising this troop…..If he can raise the horses from malignants [the Parliamentary term for Royalists] let him have your warrant.’ In this same letter Cromwell wrote ‘I had rather have a plain russet coated captain that knows what he fights for, and loves what he knows, than that what which you call a gentleman and is nothing else. I honour a gentleman that is so indeed.’ As a relatively prosperous man Margery was regarded as a gentleman in Walsham, but bore no coat of arms as did the established gentry.

In the same month Cromwell was again writing to the Suffolk Committee in reply to their complaints about Raphe Margery and his zeal in seizing horses from so-called malignants, (the cavalry were very short of horses). Perhaps an instance of an old score being settled, the Rector of Finningham, John Mayer, a known royalist, and excommunicator of Abigail from Walsham church, had his horse taken by one of Margery’s troopers. After excusing Margery for his obvious mistakes Cromwell went on to say that ‘if Margery and his troop were troublesome, send them to me, I’ll bid them welcome’. At this point Margery, now made captain, joined Cromwell’s regiment as the 13th Troop of Ironsides. He had raised 113 young men from Walsham and the near vicinity as cavalrymen for this troop.

Captain Margery, now a professional soldier, became part of Cromwell’s military division. Noted as an ‘Independent’, a moderate churchman like Cromwell, he was chosen as an officer in the New Model Army of which Cromwell was second in command. His regiment fought at the decisive battle of Naseby in 1645, and after years of service in areas from Bristol to

Edinburgh, he was at the age of nearly sixty, still campaigning in the Channel Isles. The rigours of army life had taken their toll, and when summoned to ride with his regiment to Scotland in September 1653, he was unable to attend. He died at Walsham on the 27th of the same month, and was buried ‘towards evening’ in the churchyard; his remains, with those of Abigail, lie somewhere within that plot.

A full history of Raphe Margery with references, can be found in the Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and History Vol. 36 pp 207–218 by Jean and Ray Lock, a copy of which is in the Record Office at Bury.

Jean Lock

19th Century Transportation (continued)

In the 1st issue of the Quarterly Review, I wrote of the transportation of Robert Dew to Australia for life and mentioned the six other men who were transported for seven years each. In the 7th issue, I wrote about Zachariah Pamment, Philip Finch and James Tydeman. When transported, Zachariah Pamment was newly married with a baby daughter Louisa. His wife Susan died in 1836 and I was left wondering what happened to Louisa. I now know that Isaac and Catherine Pamment, Zachariah’s parents were living at Riverside Cottage (Mr and Mrs Winch have the deeds to prove it!) and were caring for Louisa. They all appear in the census for 1841 and 1851. By 1861 Isaac had died and Catherine was living at Riverside Cottage with a grandson. Louisa had probably left to get married, but not in Walsham. Descendants of Zachariah are now in contact with us and I await further information from his great great ? grandson in Australia.

So what of the three remaining men who were transported?

Benjamin Jackaman was a maltster working for William Cornell who operated a maltings in Palmer Street (opposite Moores where a flint wall remains). He stole “7 bushels of undressed malt, 2 pecks of oats and 2 hempen sacks”. He was tried at the Suffolk Quarter Sessions at Bury on 7th March 1837 and sailed on the “Neptune” on 4th October with 350 convicts arriving at Van Dieman’s Land (Tasmania) on 18th January 1838. Stowmarket was given as his native place: perhaps he lodged in Walsham with a local family. His convict’s record states that he was 30 years of age, 5 feet 5 inches tall, of fair complexion with light brown hair and dark grey eyes. He had a scar on one finger – he was a shoemaker as well as a maltster, which probably explains it. He was married with four children. In 1840 he was accused of “being in a public house during divine service” but was acquitted it being a first offence. In 1842, however, he was given one month’s hard labour for theft and misconduct and the following year had his ticket of leave suspended for misconduct. In June 1844 he married Mary Ann Reid, a dressmaker aged eighteen years and went on to have ten more children before dying of “paralysis” near Hobart in 1879 aged seventy-one.

Henry Ellis was described as a ploughman and brewer from Diss. He was accused with Benjamin Jackaman of stealing “ 7 bushels of undressed malt, 2 pecks of oats and 2 hempen sacks” from William Cornell and was transported on the same ship to Van Dieman’s Land for seven years. He was married with three children. During the passage he worked in the fore holds being “industrious and very willing”. On arrival he was appropriated to a Mr. Gatehouse of New Town and presumably worked hard and behaved himself because he was given a conditional pardon in 1843. No further trace of him can be found. Did he return to Diss?

Edward Miller was a native of Gravesend in Kent. He was a baker and confectioner working for William Darby the baker and confectioner at what is now the Old Bakery and Bakehouse from whom he stole a quantity of flour and gingerbread. He was tried in 1821 and sailed on the “Phoenix” in November with 184 male convicts to Van Dieman’s Land arriving in May the following year. He was 27 years old, 5 feet 31 inches tall with dark brown hair and eyes. He received the harshest treatment of all the Walsham transportees. This may have been partly due to the fact that he was transported earlier than the others; conditions improved later on. However, he certainly did not learn from his mistakes. His convict’s record reads as follows –

- 13th June 1822 – neglect of duty and absents himself from his master’s premises without leave on the 12th of last month – 25 lashes.

- 8th July 1822 – repeated neglect of duty – 50 lashes.

- 11th July 1822 – stole a blanket and two sheets – 50 lashes.

- 8th October 1823 – repeatedly disobeyed orders, absconds from his master’s service on the 22nd September last taking with him a jacket and other articles, the property of his master – 50 lashes.

- 12th December 1823 – drunk in the prisoners’ barracks and neglect of duty yesterday – 25 lashes.

- 5th August 1824 – drunk and disorderly and insolence to superintendent – 50 lashes.

- 9th August 1824 – escapes over the wall of the prisoners’ barracks on Friday afternoon, absent until Sunday

- 14th March 1825 – absconds from the prisoners’ barracks on 5th March last and remained absent until apprehended near McGeiss Farm, New Norfolk by Charles Horan on Saturday 12th inst. – 25 lashes.

- 19th March 1825 – absconds from prisoners’ barracks on the 15th March and remains absent until the 17th when he is apprehended by Thomas Butcher at Beresford Creek.

- 24th April 1826 – repeatedly absents from muster G Gang – one month.

- 3rd May 1826 – for being accessory to the stealth of wheat from the mill – 25 lashes.

- 13th August 1827 – neglect of duty and “sticking” the acting gaoler – 25 lashes.

- 19th November 1828 – feloniously uttering as true a forged warrant and order for the delivery of goods with intent to defraud Captain Stewart and Peter Harrison – sent to Launceston to be further examined before Mr. Mulgrave.

- 18th December 1828 – forging an order for the delivery of goods with intent to defraud Peter Harrison – committed for trial.

- 2nd November 1829 – charged with the crimes of various fraud – charge dismissed – no previous appearance.

- 20th February 1830 – feloniously stole and took away a horse, the property of J E Briggs – fully committed for trial on 27th March 1830 – found guilty and given a life sentence.

If you would like to read more about transportation in general and flogging in particular, I suggest you read “The Fatal Shore” by Robert Hughes – Collins 1987.

Audrey McLaughlin

References

- Bury and Norwich Post 1837

- Walsham Census 1841, 1851

- Walsham Parish Map of 1817

- Deeds of Riverside Cottage, Walsham

- Convict records CON 31/25, CON 23/2, CON 27/7, CON 31/11, CON 31/29, Death Certificate RGD35/45NO.12, Marriage Certificate RGD37/3NO.1444 (from Tasmanian Archives) I am indebted to Ian Pearce, State Archivist for much of the above information.

What the Papers Said

The Post, 12th October 1803. The information against two publicans at Walsham le Willows for suffering tippling in their house on the Lord’s Day was withdrawn on their consenting each to pay 20 shillings to the poor of the parish.

In 1803 Britain declared war against France and Napoleon. On the 26th October the Post reported that in many villages Volunteer Corps were being set up and subscriptions were being taken to clothe and equip the men who joined. In Walsham John Sparke esq. gave £21, Dean Miller £10 10s and James Powell esq. £21.

The Post 21st December 1803 carried an advertisment for the post of a teacher in Walsham le Willows. “Wanted immediately after the present vacation, a young man of good character and properly qualified as an assistant in an English school. By personal application and proper testimonials a comfortable situation may be had. Apply to Mr Rogers at Walsham aforesaid”.

On 25th January 1804 the parish officers of Walsham le Willows placed a notice in the Post: “Wanted immediately. Two men for the Royal Army of Reserves to whom liberal bounties will be given”.

The Post 6th June 1804. Captain Cartwright’s Corps. Lately called Ashfield but now styled the Walsham Volunteers, met in honour of the King’s birthday and fired at the target in Badwell pits piercing the same with a great number of shots. They were then handsomely regaled with beer from the inhabitants of Badwell Ash. They then proceeded to Walsham and fired three volleys after which they were entertained by the inhabitants of Walsham with a plentiful dinner of roast beef and ale. The day concluded with the greatest mirth and festivity.