Transported For Life

On the 27th August 1845 Robert Dew from Walsham-le-Willows was transported on the Mayda with another 199 male convicts to Van Dieman’s Land (Tasmania), never to return.

Robert was thirty-five years old. He was five feet two and a half inches tall with a dark complexion, brown hair and whiskers. He had a “very great impediment in his speech” and “is a very long time in getting out his words”. He was a farm labourer, unemployed and unable to read or write.

The 1841 census shows his parents Robert and Mary Dew living at Cranmer Green probably in one of a group of cottages, shown on the tithe map of 1844, to the south-west of Green Farmhouse, and now demolished. Their sons John and James and daughter Anne were living with them, also a lodger, a bricklayer, but their son Robert was not included. Perhaps he was working away from home and lodging with another family, not unusual at this period. His parents would have been nineteen when he was born, again, not unusual.

The population of Walsham had been rising steadily for several decades, from 993 in 1801, reaching a peak of 1297 in 1851 before it started to fall again. The first half of the nineteenth century was the time when two or more families shared tiny cottages and larger houses were subdivided to accommodate several families where previously just one had lived.

Unemployment in the early nineteenth century was high. The end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 produced an influx of unskilled labour onto an already overcrowded workforce. Corn and bread prices were high and wages low, the result of post-war depression. Introduction of agricultural machinery into some areas did the work that previously kept several men employed. Whereas, 100 years earlier, many were employed in the wool industry and there was some choice of work for employees, especially during the winter, by 1845 agricultural labouring was almost the only work available for the majority of unskilled hands. One hundred years earlier farm workers had steady, regular work often living with the farmer’s family. It was in the farmer’s interest to provide well for his workers. The practice of living-in gradually declined and accommodation in the form of cottages tied to jobs became the norm. Poverty was thus removed from the landowners’ immediate vicinity – out of sight, out of mind. Families moved from farm to farm, parish to parish seeking work usually in the form of a year’s contract. With the increase in population and readily available men, farmers no longer needed to contract labour for long periods: they could take on men for a week at a time or even a day. During busy periods eg. harvest, many hands would be required but at other times most relied on charity in the form of poor relief. This was bitterly resented by the average willing, hard-working man who only wanted the opportunity to provide for his family. Before enclosure these men had a small piece of land and the right to keep a cow or sheep on the common. Poor relief was seen, not as a right, but as acceptance of failure.

One of the overseers for the poor in Walsham was Richard Gapp who lived at what is now Sunnyside with his three grown-up daughters and three servants. He owned nearly 200 acres, a mixture of arable and pasture with a small plantation of wood, all close to his farmhouse. On the night of Sunday, lst July 1844 between 12.00pm and 1.00am he awoke to find his barn, stable, sheds and pigsty alight. He hurried down and saw nine or ten people at the fire. Lord Thurlow’s engine came to his assistance together with two or three hundred people. Later, Henry Aldrich, an employee of Richard Gapp found lucifer matches (newly invented and, no doubt, a great novelty) near the burnt haulm (bean) stack which was next to the road. His house adjoined that of Robert Dew, about three minutes walk from that of Richard Gapp. Police Constable Pilbrow (of the new police force) searched Robert Dew and found matches on him. He took him to Ixworth where he (Dew) said, “others had done fires as well as him and why didn’t I apprehend them?”

The judge for the Suffolk Assizes held in Bury St. Edmunds in March 1845 “arrived in this town having been met on the road from Cambridge by the High Sheriff Henry Wilson esq. in a most elegant carriage with four beautiful horses richly caparisoned with the usual retinue.”

The jury comprised gentlemen, all landowners, including Mr Thomas Hutton Wilkinson of West House, Walsham. Robert Dew, speaking of his victim, was reported to have said, “There’s old Gapp might employ five or six more on his farm but the old scoundrel has suffered for it, for he has had two fires”. He then added “It was the most beautiful blaze I ever saw. I shall never forget it the longest day that I shall ever draw”. He had positively revelled in Richard Gapps misfortune because on the day of the fire he had gone along to his farm and jeeringly asked for employment.

The defence claimed the evidence was circumstantial and the admission of guilt was fraudulently obtained but, after an hour’s deliberation, the jury returned a verdict of guilty. Dew also admitted lighting a fire on the premises of Mr Hatten who lived at what is now Cranmer Lodge. He was sentenced to transportation for life. “The prisoner, on hearing the sentence, fainted away and appeared to suffer anguish of mind on his recovery.”

The crime was almost certainly what we would now call a copy-cat crime. The newspapers of the time were full of accounts of arson attacks and riots. There had been five fires in Walsham within a period of twelve months and the village was infamous for discontent along with Barningham and Ixworth. Walsham experienced a combination of fires, riots and strikes. Allotments were available for some of the men who had become landless after the enclosure of 1819 but most of these were at Allwood Green – a walk of one and a half or two miles from the village centre.

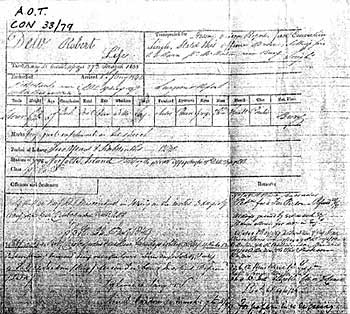

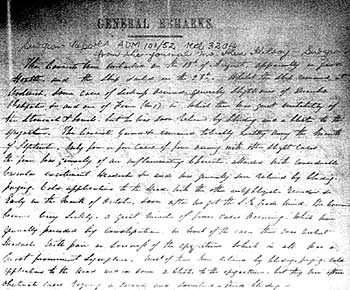

Robert was fortunate that his crime and sentence was carried out in the mid nineteenth century. A hundred years earlier he would probably have been hung. When transportation first began conditions were much harsher. The First Fleet in 1787 took 252 days to reach Australia. By 1830 the time was down to about 110 days. Between the First Fleet and the last, in 1868, 825 shiploads of, on average, 200 convicts (men, women and children) made the journey. The ships were, in the main, old ships converted, and convicts were shackled four to an area about six feet square. Disease was rife. On one boat, in 1801, sixty-five died during the voyage. But, according to the surgeon’s report, the Mayda, on which Robert was transported had a reasonable journey of 135 days with no bad weather. The most common sickness was due to bad water and diet. Constipation, diarrhoea and headaches were very common; they were relieved by bleeding, blisters, purging and cold applications to the head. Supplies of fresh meat, vegetables and best bread at the Cape of Good Hope worked wonders as did fresh water. The first supply was filtered water from the Thames stored in oak casks. Four men died on the journey plus the wife of a sergeant who died in childbirth. The ship was roomy and well ventilated. The men spent considerable time on deck during the journey. They were given lime juice to prevent scurvy. Six men were taken to hospital on arrival at Norfolk Island, two being detained. Although the newspaper reports state that Robert was sent to Van Dieman’s Land, in fact, he went first to Norfolk Island, arriving on 8th January 1846. Norfolk Island, “the worst place in the English-speaking world” had earlier been the scene of draconic punishments when starving convicts were flogged, sometimes to death, on the orders of a sadistic colonial governor, for stealing potatoes. Fortunately for Robert, by 1846 the system was better organised and supplies of food adequate. He appears to have stayed there for two and a half years before going on to Van Dieman’s Land. His convict’s report shows that he was disciplined and reprimanded (no details were given) and kept in solitary confinement for misconduct, idling and insolence on several occasions. He gained 101 days by extra work. He applied for, and was refused, a free pardon, in 1847 and, in 1852, was told he must serve twelve years from the date of conviction. But the last entry on his report is dated 1874 when he was given three months hard labour for being idle and disorderly. He would then have been sixty four years old.

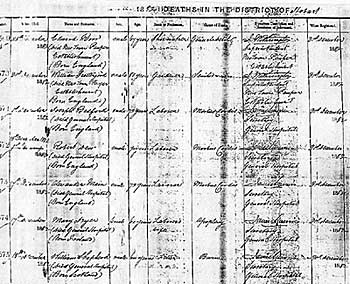

He died of heart failure in Hobart General Hospital on 15th December 1882, aged, according to the death certificate, seventy years.

I have a bit more information on the six men but would like to find out more, especially whether they returned or not.

Audrey McLaughlin

References

- Bury and Norwich Post 2nd April 1845

- Surgeon’s Report ADM 101/52 reel 3204 from the journal of Alan Kilroy, surgeon

- Convict’s Report AOT CON 33/79

- Death Certificate (Deaths in the District of Hobart)

- Walsham Census 1841

- Walsham Tithe Map 1844

- White’s Directory of Suffolk 1844

- “The Fatal Shore” Robert Hughes – Collins 1987

- “By a Flash and a Scare” John Archer – Clarendon Press 1990

- Six other men from Walsham were transported to either Van Dieman’s Land (Tasmania) or New South Wales for seven years: Edward Miller – stole flour and gingerbread from William Darby, baker and confectioner at Walsham;

- Benjamin Jackaman (a maltster) and Henry Ellis (a brewer) stole malt, oats and sacks belonging to W .G. Cornell of Walsham;

- Philip John Finch – stole feathers from George Finch;

- James Tyderman – aged 19 years – stole a peck of Windsor beans from George Finch;

- Zachariah Pamment – glazier – stole glass from mansion house of Sir James Blake.

Witchmarks

We recently noticed on some panelling in our l5th century house a wealth of deliberately scored marks. Several closely resemble marks once widely applied to protect timber buildings against the perceived manifestations of witchcraft; lightning, drought, disease etc.

The marks are typically found on bessemers over fireplaces, doorways and staircases, and aimed to impede the entry of witches or their familiars. Associated preventive magic might involve placing a cat under the floorboards near the chimney symbolically to repel familiars entering that way.

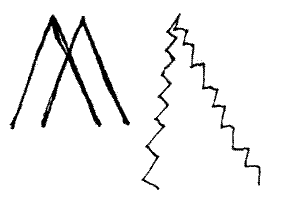

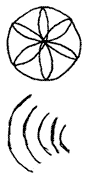

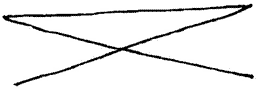

Of the motifs, many invoke the Trinity by their 3-fold nature, Our Lady (the letter M for Mary), the saints, the Holy Spirit and so on. It is well worth looking out for the marks shown and other unexplained symbols, if you have old house timbers.

When I have had an assessment of our marks from the local expert, Tim Easton, I hope to give more details.