The Folks Who Lived on Joly Cote Hill (Part One)

Having, as a child, enjoyed scouring Norfolk’s beaches for interesting shells, stones and driftwood, I was an early convert to Stanley West’s field walking survey of Walsham some twenty years ago, the results of which are now published. With Stanley’s training it was natural, when gardening, to keep an eye open for any little treasures that might reveal themselves among the flowers, vegetables and weeds of The Old Bakery in Walsham’s main street. Finding a pottery sherd, dated as Ipswich ware of the Saxon period between 650–850 AD, triggered a desire to know more of the history of this part of Walsham.

The Anglo-Saxons gave our village its name. Waaels or Wals being, perhaps, the name of the person holding this settlement or enclosure of land known as a ham. A Saxon church is recorded in the Domesday Book of Norman times. What more natural than that these Saxon cultivators, settled along the south facing slopes of a fertile valley, fixing tracks and field boundaries which, in many ways, are the same today, yet leaving little evidence of their presence here save sherds of pottery. Elsewhere of course, in the heathlands to the east of our county, at Sutton Hoo near Woodbridge, field systems, settlements and most elaborate burials have been excavated, recorded and most recently interpreted in Martin Carver’s book “Sutton Hoo. Burial Ground of Kings?”. But for Walsham we can only manage a computer reconstruction of a domestic pot from the discovered sherd. Other sherds of pottery carry the story of settlement on Joly Cote Hill forwards. There are two pieces of rim from the 13th century, two glazed and seven unglazed later medieval sherds. From the 16th and 17th centuries there are four pieces of rim, a handle and a number of other sherds.

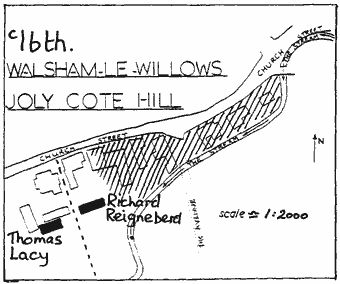

So, for several hundreds of years, settlers repaired their homes, cultivated their plots, tended their animals and paid their fines for a multitude of unsociable acts, as recorded in our surviving manor court rolls. But it is the Field Book of Walsham of 1577 which provides the first firm evidence of who lived where and what lands each held. For this part of Walsham we are clearly told:

“[41a] Lacy Thomas The said customary crofte with a tenament at the easte ende thereof in the tenure of Thomas Lacy gentleman was (as yt semethe sometymes three parcels, and lyeth toward the este betwene ye Brooke Lane in parte and a decayed cottage in the tenure of Richard Reigneberd in parte, and toward the weste betwene ye foresaid crofte and ortyarde of John Robwood the yonger in parte and the foresaid cottage of Andrew Curtes in parte/ and abbuttinge northe uppon ye Churche Waye and sowthe uppon ye Brooke Lane and conteynethe – 3 acres 3 perches” Today this corresponds to the site of the Memorial Village Hall, the car-park, bowling green, telephone exchange and the Institute.

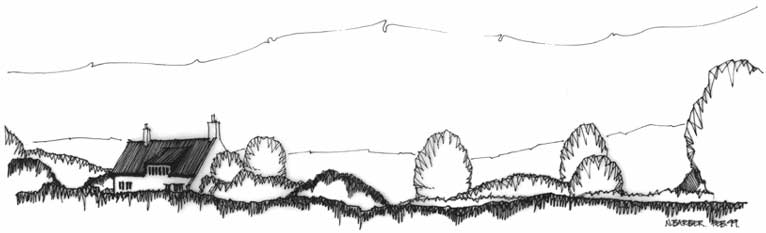

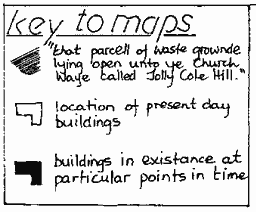

“Reigneberd Richard The said decayed cottage with a little yarde therunto adjoyninge and apperteyninge in the tenure of Richard Reigneberde lyeth este [41b] uppon a parcell of waste grownde lyinge open unto ye Churche Waye called Jolly Cote Hill, and weste uppon the foresaid tenament of Thomas Lacy gentleman north uppon ye Churche Waye and sowthe uppon ye Brooke Waye and conteyneth – 9 perchers” This corresponds to the timber framed and thatched Clive Cottage. Where The Bakehouse, The Bakery, Avenue House, School House and Eric Hubbard’s workshop now stand was: “That parcel of waste grownde lying open unto ye Churche Waye called Jolly Cote Hill”

This piece of ground seems to have extended as far as the bridge over the stream opposite Rolfes Butchers and a lane called Brook Lane followed the edge of the stream towards Grove Road.

But we cannot be sure that Richard Reigneberd actually inhabited this tenement for he held other lands, totalling some 33 acres which included some north of Fishponds Farm, some bordering Palmer Street, some on the north side of The Street, some near the Great Meadow beyond The Lawn and included a cottage called ‘Randes’ on the site of the thatched cottage in The Avenue. And although a significant landowner, he was, like the rest, subject to the jurisdiction of the manor court and in 1555 he was ordered by the steward of the court to “scour the ditch and divert the water there.” The maintenance of the stream channel was a constant problem throughout the parish and orders such as this to clean out the ditch were common.

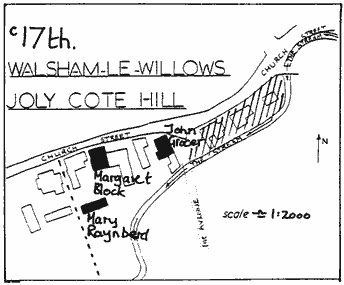

The 1695 Survey, one hundred years later, confirms the land and buildings held by Thomas Lacy and Richard Reigneberd in 1577 but also records two new ones. To the east of Clive Cottage Margaret Block held a messuage with a 1/4 acre of land and beyond this, John Grocer had a cottage called Joly Cote Hill on one sixteenth of an acre of land. Clearly “that parcell of waste grownde called Jolly Cote Hill” was filling up.

House deeds now allow us to follow the history of individual properties more closely. In 1699 Clive Cottage passed from Mary Raynberd to William Hawes, a victualler, then in 1704 to Thomas Culyer, a worsted weaver from Fundenhall in Norfolk and in 1722 to William Youngman, gentleman. It was Mr Youngman and others who, between 1728 and 1733 presented a Bill of Complaint to His Majesties Court of Chancery against Elizabeth Hunt who, as owner of The Priory, collected small tithes in respect of meadows and hay, titles which were excessive in the eyes of twenty-seven owners and occupiers of land.

Further evidence of MrYoungman’s stature is evident in his will of 1773 in which he leaves to his son “all that messuage …..abutting on the highway called Church Street ….. and that tenement now divided into two dwellings and abutting on the aforesaid messuage to the north and on the river on the south part.” In other words, Mr Youngman had built a new house between Clive Cottage and The Street which is now known as Clive House. Furthermore Mr Youngman junior was bound to pay his widowed mother £16 per year for the rest of her natural life. One of the tenants of Clive Cottage at this time was William Davie, a peruke-maker and barber. Following the death of Mr Youngman junior in 1796 both properties were quickly exchanged three times in the space of seventeen years. The transactions give us not only an insight into the mortgage business of the day but also the rapid escalation of property values.

Mr Clamp made a handsome deal and if further proof of pressure for housing is needed, note that in 1848, when the properties were next sold, the particulars describe “two substantial cottages now divided into six tenements.” But then, between 1801 and 1841 the population of the village had grown from 900 to 1200.

Meanwhile, next door, at what is now The Bakehouse, a similar succession of people occupied “all that tenement called Emmes and one cottage lying together” as it was described in 1722. This suggests that the largely clay lump, flint faced building beside The Bakehouse was constructed between the survey of 1695 and 1722 when timber was getting in short supply. The Bakehouse itself we know was already in existence in Margaret Block’s name in 1695 and the inventory of Henry Block made 17th January 1678 records that he had “in the Shopp” : two butchers axes; two cleavers; one payre of scales and weights; lumber belonging to the house.

Henry Block was a butcher who originated from Hunston. His inventory also includes five beds, blankets, three “beere vessells” and six rush bottomed chairs. In the Hearth Tax Return of 1674 he is recorded as having one hearth in Walsham.

Richard Palfrey who succeeded the Blocks in 1722 was a thatcher from Langham and he in turn sold the property for £85 to Joseph Barker, a grocer, in 1731 allowing him to repay a loan of £40 to Joseph Rust of Wattisfield which was taken out in 1725 on security of the property and for which the half yearly interest of £1.00 was paid and acknowledged with meticulous precision.

Joseph Barker’s will, made the year before his death in 1753, throws some interesting light on his different properties, his commercial involvement in Finningham Fair and on his perhaps wayward son John. Initially Joseph had appointed his son John and daughter Elizabeth to be the executors of his will, and had charged John to give £100 of goods from his inheritance to his sister Elizabeth while a second son Joseph was to give £150 of goods from his inheritance to Elizabeth. However, in a codicil, John was replaced as executor by his brother Joseph and ordered to pay an extra £50 to his sister. In the will, son Joseph received a house and land called ‘Watchhouse’ at Wattisfield. The remaining properties in Walsham and Finningham went to Joseph senior’s widow including “houses, outhouses, barns, stables and all other buildings on the several parts of my estate.” Moreover the widow was advised “to keep sufficient quantity of stuffs for use at Finningham Fayre” and to “pay the insurance to the Sun Life Office.” Upon the death of widow Barker one year later in 1754, son John received the Walsham property together with “boards, poles, tressels and other materials belonging to the fayre” only to be killed by his horse while travelling from Norwich to New Buckenham in 1763. He is buried in Swardeston churchyard and left a step-daughter Sarah Curtis, whose family unsuccessfully pursued an interest in the estate 50 years later in 1813. This required Sam Lock, Clerk to the Parish, to confirm the burial of John’s first wife at Walsham, and John Thump the churchwarden of Swardeston, John France the Minister at New Buckenham and widow Mary Townsend of New Buckenham to confirm John’s second marriage to a widow Curtis but that he had no issue by her.

In the intervening fifty years, Robert Brooks of Great Ashfield bought the property in 1766 for £105, William Bethel a plumber and glazier took possession in 1792 for £70 before making a handsome profit three years later by selling to Zacharia Simpson a maltster for £140 who, in 1814 sold to William Darby for £180 “all that messuage called Emmes and one cottage standing together.”

So, in the space of twelve months, William Darby had acquired Clive House, Clive Cottage, The Bakery and The Bakehouse. Thanks to a loan of £200 from John Lowe of Ixworth he promptly set about to “rebuild, modernise, improve and add extra buildings.” Hence the white brick façade, the Georgian windows and doorway with associated alterations at The Bakery. But all this required further loans, and a mortgage bond of 1814 shows loans now totalling £680. Nor did this ambitious man stop here. To the postmill in Wattisfield Road, he added a brick roundhouse and to its adjacent fields he added Crossway Meadow and Squirrells Hall pightle by purchase for £201 from Elizabeth Tricker of Fishponds Farm in 1836. He even persuaded the Feoffees of the Townlands of Walsham to exchange an inaccessible piece of land for their ‘Gown Piece’. Perhaps he was investing in his sons’ future but son William died aged 26 in 1837 and Joseph died the next year aged 19 years. A further loan of £750 was obtained from John Lowe in 1839. But Mr Darby’s scheming and borrowing came to an end on 8th September 1848. The solicitor, Mr Golding demanded repayment of a £170 loan with interest, within ten days, on pain of the disposal of a vital two acre strip of access land. Mr Darby did not comply and on 5th December 1848 an auction of four lots was held at the Boar Inn at 4.00pm by order of the mortgagee Mr Hustler Lowe of Reading, who sought to recoup loans now totalling £1,100.

Rob Barber

Thomasina Smalpiece

In the paving of the south aisle at St Mary’s, Walsham le Willows, is a brass shield and inscription. The shield has the arms of Smalpiece on the left, Shardelow to the right. The Latin inscription runs:

‘ANNO MILLENO, SEXCENTENO ATQUE SECUNDO POST NATUM CHRISTUM, DONEC SCRIBEBAT ELIZA BETHA REGENS QUINTUM POST DENOS QUATUOR ANNUM IANI BIS DENO, AC OCTAVO, FILIA THOME SHARDELOW QUAE FUERAT, NUPER CONIUXQUE ROBERTI SMALPIECE, HOC TANDEM POSITA EST THOMASINA SEPULCRO.’

All six lines scan as hexameters in the classical manner. The metre sometimes demands that words are in an unexpected order or even made to straddle the lines, as in ELIZABETHA. Fanciful poetic style yields phrases such as BIS DENOS, twice a half-score, instead of the usual VIGINTI for twenty. A literal translation is unreadable and the following is in the style of Elizabethan rhyming pentameters:

‘WHEN SIXTEEN HUNDRED ANNUAL ROUNDS AND TWO HAD PASS’D SINCE OUR LORD’S BIRTH, AS HE FOREKNEW, ELIZA FIVE AND FORTY YEARS HAD REIGN’D; DAYS TWENTY-EIGHT HAD JANUS’ MONTH OBTAIN’D; TOM SHARDELOW’S CHILD, AND ROBERT SMALPIECE’ WIFE, THOMSIN AT LAST CAME HERE, BEREFT OF LIFE.’

This, in its turn, is nearly as obscure as the Latin, and needs a commentary. The six lines form one long sentence. In other words, on 28th January 1602, in the 45th year of Elizabeth’s reign, Thomasina, her status recorded in line 5, was buried. The parish register gives the common form Thomsin, often, as here, a daughter of Thomas.

In 1ine 2 occurs DONEC SCRIBEBAT, literally ‘up to the time when he had written’. This refers to Christ writing a foreordained scheme for the years. Formerly a year began with Christ’s conception nine months before Christmas Day, March 25th. When Thomasina was buried in late January, the year was still considered 1602, although by our reckoning the year had changed to 1603 on January lst.

The 45th year of Elizabeth’s reign began in November 1602 (both reckonings), the anniversary of her 1558 accession. She died on March 24th, the last day of 1602 by the old reckoning, but in the third month of 1603 by ours. Elizabethans were fascinated by numbers, and 1602, 45, 28 are multiples of 6, 5, and 4 respectively, although the significance of this grouping is elusive.

Of Thomasina herself we are told little. Buried inside the church, she was a member of the gentry as is also attested by the heraldry. She was married, and elderly as implied by her burial being TANDEM, ‘at last’. According to the parish register she was buried on January 30th, not the 28th, perhaps the day of her death. Had the poet known of the 30th he might have written of a triple trinity, 1602, 45 and 30 being divisible by three.

Brian Turner

What the Papers Said

The Bury Post of 10th February 1802 gave notice of – “To be sold. About 18 tons of upland hay and about ditto of clover – apply to Mr Zachariah Simpson of Walsham le Willows.”

8th September 1802 – “For sale or let. A neat dwelling house in Walsham le Willows consisting of a parlour and kitchen in front, a back kitchen and pantry, four bed-chambers, stable and other out-buildings, a small garden of about 1/2 acre well planted with fruit trees. The premises are in good repair and have been newly built within a few years. At present in the occupation of Mr. Kemble, surgeon who will show the premises.”

13th October 1802 – a horse was reported as being stolen or strayed – “From the pasture of Robert Runnicus of Walsham le Willows on Monday night went missing a sorrel gelding., seven years old about fifteen hands high, full mane and tail, a small shim on his face and a few white hairs at the top of his withers occasioned by the collar. If stolen a 25 guineas reward on the apprehension of the offender, if strayed reasonable expenses paid.”

24th November 1802 – “As an instance of the mildness of the season bats were seen hovering about Walsham le Willows on Saturday night in as many great numbers as during the hot weather in summer.”