Last Day At The Vicarage 1859

One of our members, Michael Marland, has kindly let us see an 1859 sale catalogue relating to The Priory. In 1902 it gave its name to the building nearby in which we have our meetings, The Priory Room.

The Priory at Walsham was an offshoot of the great Ixworth Priory established in the 12th century. Ixworth supplied priests for several parishes in this area, and the Walsham building was a base for chaplains who ministered in St Mary’s church. When Ixworth Priory was dissolved in 1538, our outpost continued in use as the Anglian priest’s residence. It still served this purpose in 1859, but, as implied in the catalogue, it was not very suitable for Victorian vicars, often with large families. Some time after 1859 a more extensive property, Spilmans on Palmer Street, was adopted as St Mary’s vicarage. This house in its turn was seen as inconvenient, being a long way from the church. In 1904 John Martineau, Patron of The Living, virtually rebuilt The Priory, nearly doubling its size, so that it could again be acceptable as a vicarage. Most of what we see today, a seemingly medieval timbered building, is in fact Edwardian. With the parson’s residence reinstated at The Priory, Spilmans came to be known, in confusing Walsham style, by its present title “The Old Vicarage”. To round off this tale, in the 1990s The Priory was seen as unsuitable as a rectory. The Diocese bought the present Rectory on The Causeway, selling The Priory as a private dwelling.

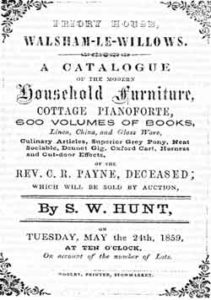

Back to the 1859 catalogue; it is an octavo-sized booklet, the cover using many different printer’s founts, and decorated at the corners with printer’s ornaments. This florid display advertises the versatility of “A.B. Woolby, Printer, Stowmarket”. Setting aside the showmanship, the title page tells us that there is “a catalogue of the modern household furniture, cottage pianoforte, 600 volumes of books of the Rev. C.R.Payne, deceased”. Because of the many Lots, the sale by S.W.Hunt on May 24th 1859 was to begin briskly “at ten o’clock”.

We know very little about Mr Payne. From the Parish Register we gather that his christian name was Charles, that his incumbency began in 1852, (the year before the Martineaus came to The Lawn), and that his ministry ended with his death in 1859. He was not buried at Walsham. From the details of the catalogue it appears that he was not a rich man, comparatively speaking, and, if he left a widow, she would have been obliged to leave The Priory for the next incumbent.

Interestingly the prices realized have been written in the margins. Humble details are entered from every part of the house. For example in “The Attics”: “night commode and warming pan. (7s.0d)”. Among the “Outdoor Effects” was a “dennet gig”, somewhat outmoded by 1859, which realized £9.5s.0d. It was pulled by a “handsome grey pony, fast and quiet in harness, neat, sociable”. This realized the most money in the whole sale:7pound;16s.

A pony and gig were necessary tools of the trade in a parish as far-flung as Walsham. Other “tools” were the books, 600 volumes forming 93 Lots, occupying four pages of the slim catalogue. They were listed under the contents of the dining room, there being no separate study, and it appears that Mr Payne prepared his sermons on the mahogany dining table (£3.15s.0d). Many of the books went for knock-down prices, and presumably they were not in good condition. An instance of the pitiful amount realized, one of many, is “Lot 129: Greek lexicon, 2 vols. and 6 others(1s.6d)”. Charles Paynes library held the usual biblical commentaries, concordances and devotional works, including, amusingly for us, “Blair’s Sermons, 3 vols.”. Apart from theology there were editions of Herodotus, Euripides, Suetonius and Ovid, but no Homer or Virgil, which were the usual components of a classical library. For English authors, Shakespeare and Dr Johnson were well represented, but contemporary popular authors such as Dickens and Thackeray were only hinted at in “sundry volumes of books”.

The drawing room was presumably where a lady held sway. Here was the “mahogany ladies” work-table (14s.0d.)” and a “mahogany what not” (£1.15s.0d.). This was a luxury item, a set of shelves to hold ornaments. Amidst all the precise detals of household items, the fish-kettles, fire-irons and floor-cloths desperately sold for shillings, there was no mention of drawing-room keepsakes or pictures. Similarly, the cottage pianoforte, announced in large letters on the cover of the catalogue, was unmentioned among the Lots. Perhaps some other arrangement had been made, a private sale, or maybe a gift. One is reminded of the mysterious piano in Jane Austen’s bittersweet novel of 1816, “Emma”. Victorian reality was probably grimmer for Mrs Payne. We can assume that Charles Payne’s death was unexpected because a drawing room Lot which realized an appreciable sum was a “large brussels (sic) carpet, nearly new (£8.8s.0d.)”. The vicar would not have made such an investment if he had thought his death was imminent.

As stated earlier, we know little about Charles Payne. His incumbency of 1852 to 1859 means that he slips between the Censuses of 1851 and 1861, and his obituary cannot be found. We do not know whether there were any sons or daughters. There was a well appointed “Chamber No.1” holding “a four-post bedstead, mahogany pillars, drab morine furniture (£3.5s.0d.)”. “Drab morine furniture”, incidentally, means that the bed hangings were of a stout warm material in a restricted colour. The bedstead was fitted with an expensive “hair mattress (pound;2.10s.0d.)”. There were three other upstairs bedrooms (Chambers 2,3, and 4) with similar, less expensive, furnishings. Allthough family is implied, these rooms may have been for guests.

There is evidence of a servant, for downstairs there is a “kitchen chamber”. Like the upstairs rooms, it had a fireplace, foot bath and wash stand. There was a simple “tester bedstead, green furniture (7s.0d.)”, that is, bed-hangings dyed in a cheap colour, but there was a good quality wool matress(15s.0d.) and a feather bed (£1.5s.0d.). Surprisingly, in this kitchen chamber, there was a “mahogany chest of drawers (£2.16s.0d.)”. This last item was written in as an addition, perhaps to raise as much money as possible. The total amount for the sale was £300.11s.6d. It all seems a sad business. In some ways it is reminiscent of that large painting in Tate Britain: “The Last Days in the Old Home” by Robert Braithwaite Martineau, cousin to our family at The Lawn. The painting, finished in 1861 after years of work, was on the easel at the time of the Walsham auction. It deals with the results of drink and gambling, but it also poignantly shows the trauma of a forced sale.

Brian Turner 2007

Since the printing of ‘IT IS WITH DEEP REGRET’ more information has come to light about some of the soldiers from Walsham who died in the battles of the First World War.

Lawrence Robathan

The yougest son of Arnold and Laura (nee Holmes) of the Woodlands was born in Staffordshire and educated at Handsworth Grammar School and later in Bury St. Edmunds.

He joined the London Regiment in 1915 and fought on the Somme. He later became an officer in the Leicester Regiment and was with them on the front line in Flanders. On 26th September 1917 he was wounded in action and died two days later aged 20.

His Commanding Officer wrote:

‘Second Lieutenant Robathan had not been with us long but during that time he showed himself to be a keen and good soldier. He took great interest in his men and his charming personality made him popular with all ranks. He was doing fine work and his name has been sent in for the Victoria Cross and I hope he gets it.

I had a talk with him the morning before the advance and I was impressed by his mastery of the situation and his cool and collected bearing under circumstances of great difficulty. His loss is a great one.

He died a hero’s death. With two other men he charged an enemy strong point through our own artillery barrage and took the position. He was such a nice chap and we were all fond of him. I wish there were more like him.’

Lawrence was mentioned in Despatches by Sir Douglas Haig. (London Gazette 18th Dec. 1917). for gallant and distinguished services in the field. He was buried at Dozingham Military Cemetery, Westvleteren, Belgium.

Lawrence Clamp

The youngest son of village grocer and draper William Clamp and wife Alice (nee Hayward). He was educated at the East Anglian School in Bury St. Edmunds and at Goldsmith College in London and became a school teacher. It would seem that he met Beatrice Philpot whilst working at the school in Great Gidding. They married at Hernhill Church in Faversham, Kent in June 1914.

At the beginning of the war he joined the Royal West Kent Regiment. In 1916 the couple had a son named Lancelot. In August 1918 Lawrence was killed in action in the Somme region of France to the east of Albert. He was buried in the cemetery at Becourt near where he died. He was commemorated at Walsham on the brass plate next to the north door.