The Earthquake of 1580 and William Withers of Walsham

The early evening was calm and clear on the 6th April 1580, when suddenly without warning an earthquake struck England from York southwards, extending across the continent as far as Cologne. The tremors caused masonry to fall, the church bells to ring and the sea became very rough causing ships to founder. It was the Wednesday of Easter week, and in London many people who were at church services were injured as they climbed over one another in their efforts to escape into the open. During the succeeding weeks several more tremors were felt, the last of them being on May lst. Although fatalities were few, the earthquake generated great fear among the population that divine providence had caused this disaster in order to rebuke them for their sinful way of life.

This prompted the Privy Council to write to the Archbishop of Canterbury (Edmund Grindal) asking him for spiritual guidance. He advised people to go without one meal a day, converting this into alms for the poor. For his part, he would compose a new prayer book, which he exhorted all parishes to purchase. He also asked all parish priests to urge their parishioners to come devoutly to church on Wednesdays and Fridays to listen to a short sermon on repentance. Furthermore he asked all householders to lead family prayers at night asking God “to show mercy to us who have deserved his anger”.

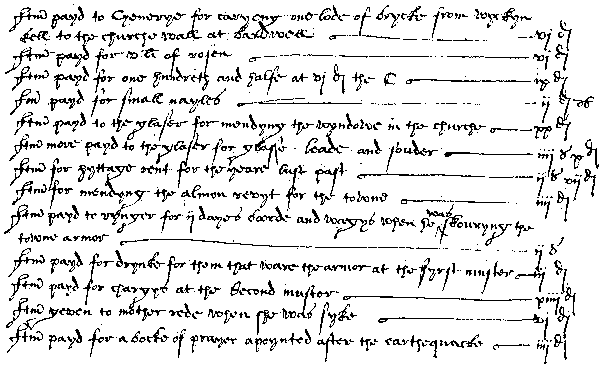

Two documents have survived which tell us something of the effect of the earthquake in this part of Suffolk. The first is the Townwardens’ Accounts for Bardwell. At the top of the document (written in a slightly later hand) are words the “1580 in which yeare was the Earthquake”. The accounts record several items paid for repairs to the church for that year, which suggest quake damage. A more telling entry states “Item, payd for a bocke of prayer apoynted after the earthquake – 4d”, indicating that parishes had heeded the Archbishops’ injunction.

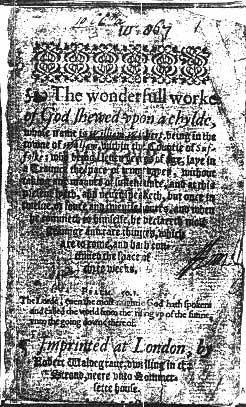

The second document is a three halfpenny pamphlet in tbe octavo format very popular with Elizabethan publishers. It described “The wonderfull worke of God shewed upon a chylde”. The child in question was William Withers of Walsham le Willows, aged 11 years, who, on the previous Christmas Eve had fallen into a deep trance which lasted 10 days “to the great admiration of the beholders, and the greefe of his parentes”.

It was reported that during this time he took no sustenance, and that on regaining consciousness he proceeded to denounce contemporary sin and immorality, calling people to “spedie repentance”. Reminding them of the late earthquake, “when the Lord passed you by as it were but with one touche of his finger”, he ranted that “if there was no change in their sinful way of life, there would be far greater earthquakes when the Lord would shake the houses on their heads and make the earth open and swallow them up”. With Puritan zeal he denounced drunkenness, adultery, Sabbath breaking, swearing, excess in dress, men masking as animals (a reference to the Mummers who wore animal heads at Christmas), and actors strutting about the streets. In the last item he was referring to the Game Place, an open-air theatre in Walsham where plays were performed, When William sat up in bed and made these prophetic denunciations it was said that “his voice was so powerful that the bed shook”.

People came from far and wide braving the winter weather to see this child prodigy. James Gayton, a well known contemporary preacher, came from Bury and examined William in his knowledge of the scriptures, and found him word perfect. Such gentry as Sir Robert Jermyn, Sir Robert Ashfield and Sir William Spring also came; they were Puritans, well known for their aspirations for reform of the church. Although William was faced with these august gentlemen who were fully in accord with his religious sentiments, he was not abashed and treated them to the same lambasting as any other of his visitors. Sir Robert Ashfield made a second visit, this time with some members of his household, and of them, a man named Smith, was very fashionably attired and was described as wearing “a monstrous ruff” which was noticed by William. This precocious boy attacked him saying, “it were better for him to put on sackcloth and mourn for his sinnes, than in such abominable pride, to pranke up himselfe like the divel’s darling, the very father of lying and pride”. Shamefaced, Smith burst into tears, tore the band which held the ruff from his neck, and took a knife and cut it into pieces, vowing never to wear the like again.

In time the fame of William Withers spread, reaching a publisher and printer, named Robert Waldegrave, working in the Strand in London. He procured the services of John Phillips, a writer of religious pamphlets, to write up the story using William’s own words. This pamphlet now in the British Library is probably the only surviving copy of a large number printed. Waldegrave, recognising this as a profitable venture, sold the rights of the pamphlet to another printer called Edward White, whose editions reached as far as the Welsh border. A Master Watkins wrote a ballad on the subject which White also printed.

This was fame indeed, and the public, having an insatiable appetite for news of this kind, were doubtless agreed that the earthquake had indeed been a warning from God, who had spoken through William Withers as his medium.

Dr. Alexandra Walsham in her thesis on Providentialism has pointed out that people of this time perceived childhood as a stage in life when they might have flashes of divine insight. She states that “miscellaneous evidence attests to a more widespread impression that individuals who had not reached adolescence were capable of closer mystical communion with God than adults”. In 1579 a young German girl, reputedly resurrected from the dead, was also the subject of a pamphlet. Her denunciations, forebodings and warnings bear a remarkable resemblance to those delivered by William, and as this pamphlet was translated into English and printed in London four months before William fell into his trance, one must wonder if he was aware of its existence, and of its contents.

At this point let us return to Walsham and the Withers family. Surviving records show that villeins of that name had lived there since at least the l3th century. William’s father, also William, was a husbandman and was described in the pamphlet as “of good name and fame”. There were eight children in the family of whom William was the eldest survivor; they lived in Upstreet (now Crowland Road). When his father died in 1606 he left £10 “for the good education and bringing upp of the poore sort of children in Walsham in good nurture and learninge”. This was a large sum of money for a small farmer to leave outside his family in those days, and it prompts one to ask a number of questions. How did his parents cope with the influx of visitors crowding into their home? Did his father benefit financially from William’s fame? Were people charged to enter the house and listen to this precocious child as a sort of peepshow? Whether or not William Withers senior became more prosperous because of this event, it was a worthy thing to do to help the poor in this way. A covenant drawn up by the trustees states that he made the bequest because “of the love and zeale which he did have for Walsham”.

![“1580 – [two unreadable words] year was the Earthquake” then some more lines in unreadable handwriting (because of the quality of the image) including “Bardwell” possibly.](https://www.walsham-le-willows.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/extracts-bardwell-townwardens-accounts-1580-1.png)

The experience seemed to have done him no harm as he lived to the age of 79 years. In 1587 he went up to Corpus Christi College, Cambridge and was ordained a priest in 1594. He became Rector of Ickworth in 1595 and a year later was married to Alice Athill in Denham. This union produced seven children, but sadly in 1613 two of his children and Alice his wife died and were buried at Ickworth. In 1616 he became Rector of Wetheringset and held this living until his death.

He survived all the upheavals in the church in the early part of the l7th century, when many incumbents were deprived of their livings because of their religious beliefs. William Withers was not one of those unfortunate people. He may have decided to lead a quiet life, surrounded by his books; his Probate Inventory lists a large library. Sometime during his long life he remarried; his second wife was a widow, also called Alice. This marriage was childless. His eldest son William became Rector of Thwaite, and his second son, James, became a Doctor of Medicine practicing in Ipswich. William left James all his “Physic Books”, an indication perhaps that be was interested in medicine because of the extraordinary events in his childhood. In later life he kept only a furnished room in Wetheringset and became an absentee priest living in a large house at Stow Bedon, Norfolk, where he died.

Jean Lock

References

- Hollinshed’s Chronicles Vol. IV. pp.426–7

- The History of Edmund Grindal by John Strype (1821) pp.369–70

- The History of Queen Elizabeth by William Camden p.215

- The Puritan Classical Movement in the reign of Elizabeth I by P. Collinson. pp.323–345 & pp. 860–930 John Phillip. The wonderfull worke of God shewed upon a chylde whose name is William Withers. (London 1581) British Library Classmark – 697 .c.87

- The Townwardens’ Accounts of Bardwell. SRO (Bury) FL 522/11/22

- Edward Arber (ed.) The Register of the Company of Stationers of London 1554–1640. vol. Il. 386

- W. Withers’ Baptism 4 Apr. 1568. SRO(B) FL 646/4/1

- Lay Subsidy. E. Powell 1910. A Suffolk Hundred in tbe year 1283

- Covenant. W. Withers senr. 1606. SRO(B) FL 646/11/92

- Dr. A. Walsham. Prophecy, Puritanism & Childhood in Elizabethan Suffolk. Trinity College. Cambridge Marriage of W. Withers to Alice Athill. Boyds’ Marriage lndex. SRO(B) J 589/1

- The Game Place, described in detail in The Field Book of Walsham, Dodd (ed). Suffolk Record Society Vol. XVIl. p.92

- J. & J.A. Venn. Alumni Cantabrigiensis. Part 1 to 1751. Vol. IV

- Will, W. Withers. clerk. Norfolk Record OfFice (Norwich) 127 Barker (MF.93)

- Probate Inventory of William Withers NRO (Norwich) INV. 48/154. 1647

- Eyriak Schlichtenherner. A Prophesie uttered by the daughter of an honest Countrey man called Adam Krause, (London,1580)

Incumbents of St. Mary’s Church, Walsham compiled from parish registers, wills, inventories, etc.

| 1555 | Thomas Pye |

| 1557 | John Walden |

| 1557 | John Washer |

| 1577 | John Townesend |

| 1578 | William Atwell |

| 1580 | Ezechias Morley |

| 1588 | Thomas Smyth 1907 Charles S. Ward |

| 1604 | Phillip Gooch 1913 Arthur C. Briggs |

| 1619 | Thomas Curre 1954 W. Rowe |

| 1621 | William Morton 1958 R. H. Craig |

| 1623 | Edward Voice 1962 Donald C. H. Swain |

| 1628 | Thomas Haymes 1970 John Rutherford |

| 1636 | William Hall |

| 1652 | Thomas Curre |

| 1662 | John Browne |

| 1667 | John Simpson |

| 1675 | Richard Griggs |

| 1685 | George Doughty |

| 1704 | Stephen Cancellor |

| 1721 | Mr. Craddock |

| 1748 | Mr. R. Wilson |

| 1754 | Thomas Howe |

| 1755 | James Safford |

| 1758 | Humphrey Primatt |

| 1759 | John Heigham |

| 1813 | Joseph Lawton |

| 1816 | Thomas Lawton * |

| 1840 | Thomas Lawton * |

| 184? | Samuel Golding |

| 1849 | George H. Richards |

| 1852 | Charles Peers |

| 1859 | Rowland Ingram |

| * plus Arthur Rogers who was a curate at Sapiston – died 1840 |

| 1868 | Michael T. Du Pre |

| 1871 | John Cornwall |

| 1876 | Arthur G. Lee |

| 1879 | Edward H. G. Norcock |

| 1887 | Charles D. Gordon |

| 1901 | A. L. Harrison |

| 1907 | Charles S. Ward |

| 1913 | Arthur C. Briggs |

| 1954 | W. Rowe |

| 1958 | R. H. Craig |

| 1962 | Donald C. H. Swain |

| 1970 | John Rutherford |

| 1986 | John Wood |

| 1996 | Martin Clarke |